2.1

In order to understand the reasons for high levels of under-trial detention in India, we set out to study the nature of bail decision making in the trial courts – the primary site of bail decision making. Our budget allowed us to focus on a single state. We chose the State of Karnataka.

As per the Crime in India Report, 2017 released by the National Crime Records Bureau, Karnataka ranks 13th in terms of overall crime rate in India. At the same time, Karnataka ranks 13th in terms of overall prison (over) occupancy, recording an occupancy rate of 107.9 as per the Prison Statistics Report, 2016. 71% of Karnataka’s prison population comprises of under-trial prisoners.

2.2

We undertook this study of bail decisions in Karnataka for a period of six months beginning from mid-April 2017 to mid-October 2017. In order to ensure a representative sample of cases, we chose three districts from three different parts of the State i.e. Bengaluru Urban, Dharwad and Tumakuru.

2.3

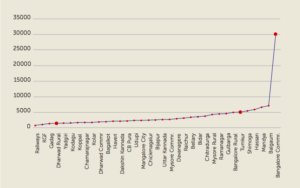

Figure a shows the average crime rate per district in the State of Karnataka from 2010-2013. We chose one district with a low average crime rate (Dharwad) and two districts with high average crime rates (Bengaluru and Tumakuru).

2.4

Bengaluru is the capital of Karnataka and is a metropolitan city, while both Dharwad and Tumakuru are smaller urban centres located in the north and south east parts of the State. Further, Tumakuru is a high crime district when compared to Dharwad, with Bengaluru recording the most crimes among the three districts. (Figure a).

2.5

As we adopted random sampling techniques to select courts and cases, we had to ensure that we had an adequate number of observations in each district. Courts in both Tumakuru and Dharwad receive several cases from the neighbouring rural

and semi-urban pockets around the cities, providing a mix of cases for the study. Therefore, the three districts represent varying levels of reported crimes, urbanisation and are also likely to present a variety of criminal offences.

2.6

This study adopts a mixed method analysis of data on bail decision making in lower criminal courts through Court Observations (qualitative) and review of Court Records (quantitative).

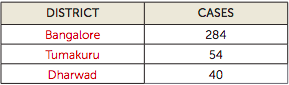

The first phase was to carry out ‘Court Observations’ over 45 days in ten Magistrate courts chosen randomly in each district, where we observed all cases where accused persons were produced for the first time in court.

This helped us gather data on whether accused persons were produced in court in handcuffs, whether they had engaged a lawyer, the extent of their interaction with the court, and the approximate time spent on each case by the judge. When courts were selected through this ‘equal probability sampling’ method in these districts, we found that only five and eight of the ten courts were functional in Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively. Therefore, two additional Magistrate and two additional Sessions Courts were chosen for Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively.[1] We observed the following cases in each district:

2.7

CLPR designed the questionnaire for the Court Observations and partnered with law schools in all three districts to engage law students as interns for a period of six weeks. The team conducted a one-day training workshop for the interns, to guide them on conducting the Court Observations and to familiarize them with the courts in the respective districts. The interns personally observed all first production cases in the identified courts and filled in questionnaires over a period of 45 days in each district. To further ensure that all first productions before the courts were covered, case numbers from the court records were verified independently on a weekly basis. The questionnaire for the Court Observations is annexed to this report as Appendix – A.

2.8

Next, ‘Court Records’ were procured from the selected courts over a period of 6 months. While Court Observations data allowed us to gain insights into the process of first production, Court Records were procured to understand bail decision making throughout the pre-trial process.

Court records reveal details such as the case number, number and details of the accused, date of arrest and first production, bail orders, and any other orders.

2.9

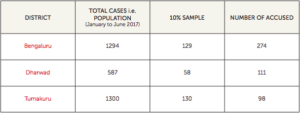

Initially we set out to obtain court records of first production cases from January 2017 to June 2017 from the FIR Register maintained by the pending branches of identified courts. To procure these court records, we prepared notarised affidavits and filled up ‘third party application’ forms for the selected cases. The FIR Register in the Bengaluru courts clearly recorded first productions. However, in Dharwad and Tumakuru, the FIR Register was not limited to first production cases and contained all cases before the selected courts for that period. Hence in Dharwad and Tumakuru, we collected court records of all cases registered from January 2017 to June 2017. To this extent, the cases listed in Bengaluru cover a narrower range of first production cases, while the records from Dharwad and Tumakuru cover all cases.

2.10

Thereafter, we sorted the data month wise and generated a random series of the crime numbers that we sought to study for each district. A 10% random sample was chosen from each district to represent the entire population. A separate and distinct coding sheet was designed to record data collected from court records, which is annexed to this report as Appendix – B. Therefore, we procured, coded and analysed the following number of records in the three districts (Table 2):

2.11

As bail decisions in criminal cases may affect individual accused in a single case differently, we chose the accused as the appropriate unit of analysis rather than the case. For both parts of the study, each question from the questionnaire in Appendix – B was coded and plotted for empirical analysis based on which questions for analysis were framed and shared with an external data analysis team.

2.12

We did not pool the data obtained from the Court Observations and Court Records phases. Although the data is not identical, it is broadly comparable as they were obtained from the same courts in the same districts and within the same time period. The main point of difference is that the Court Observations data is restricted to first production cases while Court Records cover the longer trial period.

2.13

The court records maintained by lower criminal courts in the three districts were often incomplete or contained limited information on the case. For instance, the reasons for granting or rejecting bail were often not evident from the court records. This could impact the accuracy and completeness of the data collected from the court records. The Court Observations phase attempted to overcome this limitation through in-person recording of data based on court proceedings, which was conducted by a diverse team of students overseen by on-site supervisors and the CLPR team. However, court proceedings are often unclear and inaudible, leading to observational errors. We tried to overcome this limitation by confirming the observations made with the respective court records maintained by the Registry.

2.14

Despite these limitations, a mixed method approach to data collection through the Court Observations and Court Records phases allowed us to gather data on bail decision making that would otherwise have not been readily apparent from the court records alone, such as whether an accused was handcuffed while being produced and the level of interaction between the court and the accused. As a result, we were able to compare and develop a sharp insight into the process of bail decision making in lower criminal courts.

References

- Courts that were not functional were those courts who which either a judge or a police station was not assigned. ↵