6.1

In Chapter 4, we introduced the distinction between the pre-trial and under-trial stages of the criminal justice process, with a view to understand why and how bail decision making and the factors influencing it should differ in each stage. In Chapter 5 we focused on bail decision making at first production hearings, which is the first stage of intervention by courts in the pre-trial stage. In this chapter we turn to the records of cases procured from courts (Court Records) in the three districts.

6.2

Official records disclose the manner in which a case progresses, and the timeline of events in the case. This includes, for instance, the First Information Report (FIR), the dates of hearing, the outcome on each date of hearing, when the accused was granted bail, reasons for granting or refusing bail, and conditions imposed when bail was granted.

6.3

As we noted in Chapter 5, the Court Observations data only indicated outcomes at the stage of first production as well as the relationship between bail decision making and each of the identified substantive and procedural factors at that stage. However, the Court Records data set collected over a period of 6 months, aided in developing a wider account of the pre-trial stage through the prism of bail decision making. It goes beyond first production to indicate the influence of the identified substantive and procedural factors different stages of the criminal justice process in the pre-trial phase. Further, the Court Records data would help us confirm or cast doubts on the findings of the Court Observations.

6.4

However, the analysis in this Chapter must be caveated by the fact that the data across the three districts is not comparable. As set out in Chapter 2, while the official case records obtained from Bengaluru courts were limited to first production cases, the records obtained from Tumakuru and Dharwad courts included all cases for the 6 month period, including first production cases and cases where no arrests were made or where an accused was granted police bail. A further consequence of the inconsistencies in record keeping in the three districts is that the number of accused who have formed the basis for analysis did not remain constant for every factor. However, while there was inadequate data from Tumakuru and Dharwad on first production cases, the data collected helped develop a broader perspective on the criminal justice system.

6.5

The differences in the scope and comparability of the data suggest a different structure for this Chapter, when compared to Chapter 5. Due to differences in record keeping practices in the three districts, a simple comparison of bail decision making in the three districts could not be undertaken. Therefore, in the first part of this Chapter, we compare bail outcomes from the Court Observations and Court Records data sets of first production cases in Bengaluru. Then we turn to an analysis of bail decision making at the pre-trial stage in Bengaluru based on the Court Records data. In the second part of the Chapter, we analyse the records obtained from lower courts in Tumakuru and Dharwad, which were not limited to first production cases, to explore bail decision making in the criminal justice system more generally.

A. First Productions and Pre-Trial Bail in Bengaluru

6.6

129 records of only first production cases were procured from the sample courts in Bengaluru, which named 274 accused persons. The unit of analysis for this study is every individual accused rather than each case, as different accused in the same case could be treated differently.

6.7

Based on the court observations study, we identified a set of factors that affected bail decisions at first production, which are equally applicable to the overall pre-trial stage as well. We tested the influence of (i) substantive factors such as the statutory basis for the offence (IPC v. SLL), the nature of the offence under the IPC, and the type of offence or its classification as bailable or non-bailable and (ii) procedural factors such as the availability of legal representation and due process considerations. In this section, we begin by comparing bail outcomes based on the Court Records and the Court Observations data and explore the effect of these factors on bail decision making in Bengaluru.

I. BAIL DECISIONS AT FIRST PRODUCTION IN BENGALURU – COMPARISON OF DATA SETS

6.8

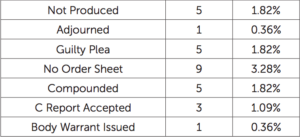

At first production, outcomes in respect of a little over 10% of the accused were different from the three main outcomes of bail, judicial custody and police custody. These other outcomes included failure of the police to produce an accused person, adjournments, compounding as well as cases where no order sheet was available (Table 12).

6.9

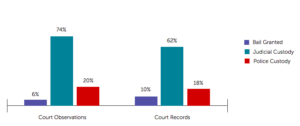

If we exclude these other outcomes, we find that on first production before a Magistrate in Bengaluru, nearly 10% of the accused were granted bail.

Around 3 out of every 4 accused were remanded to judicial custody and the remaining 20% were remanded to police custody.

6.10

Minor variations were observed in bail outcomes between the Court Records and Court Observations data sets. Nearly twice as many accused received bail in the Court Records cases and 12% fewer accused were remanded to judicial custody.

6.11

Of the various substantive and procedural factors identified in Chapter V, three factors were noted as driving bail outcomes – the statutory basis and nature of the offences, the type of offence (its classification as bailable and non-bailable) and availability of effective legal representation. The Court Observations data set presented interesting results on how a bail decision might vary depending on whether an offence is registered under the IPC or an SLL and depending on whether an accused is represented by a lawyer. Following from these findings, we will test the impact of these factors on bail decision making using data from the court records, and we will compare the results with those from the Court Observations study.

(a) Substantive Factors: Nature and Classification of Offences

6.12

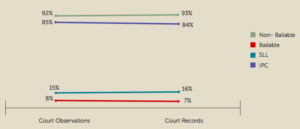

A brief overview of the statutory basis and nature of the offence as well as the type of offence in the Court Records data confirms that with respect to Bengaluru, the proportion of cases in the Court Observations and Court Records is closely aligned.

6.13

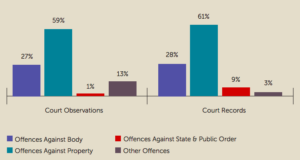

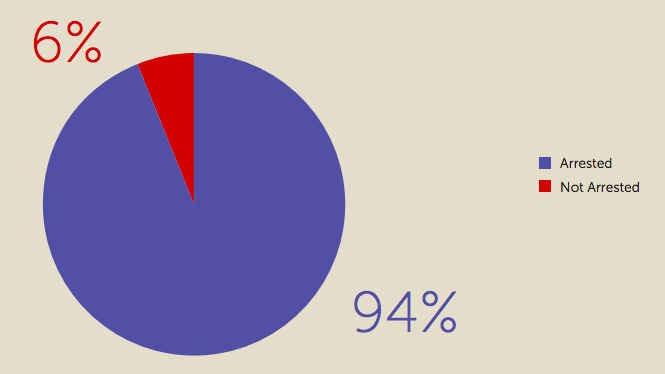

IPC cases constituted about 85% in the Court Observations and Court Records cases. Further, 93% of the accused produced in court were arrested for a non-bailable offence, and only about 7% were arrested for bailable offences, as per the data gathered from the court records, which matched the figures of the Court Observations study (Figure x).

6.14

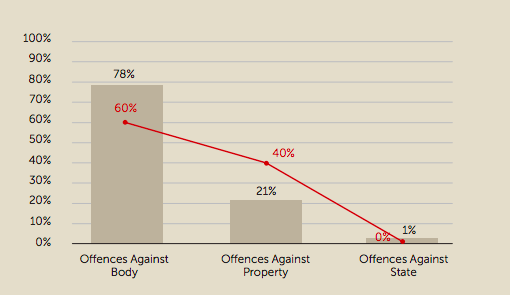

Nearly 60% of the IPC offences related to property i.e. offences of theft, robbery, and criminal breach of trust, followed by offences against the body. Offences against the State and public order comprised only 9% in addition to a small percentage of ‘other’ offences, which were largely a combination of offences against the body and property (Figure y).

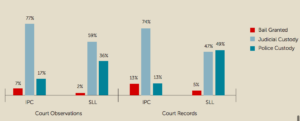

Figure z: Outcome of First Production in IPC and SLL cases in Bengaluru[1]

Figure z: Outcome of First Production in IPC and SLL cases in Bengaluru[1] Figure aa: Outcome of first productions in Bailable and Non-Bailable cases in Bengaluru[2]

Figure aa: Outcome of first productions in Bailable and Non-Bailable cases in Bengaluru[2]6.15

As the statutory basis, nature of the offence and type of offences are similar across both data sets, we may expect the bail outcomes to be aligned as well. However, bail was twice as likely to be granted at first production in the Court Records cases when compared to the Court Observations cases, irrespective of the statutory character of the offence.

In both data sets, bail was granted at nearly three times the rate for IPC as for SLL offences (Figure z). Notably, in the Court Records data, almost 50% of those accused of SLL offences were remanded to police custody.

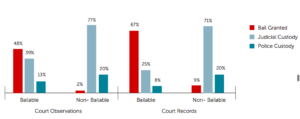

6.16

In Chapter 5, we noted that bail outcomes varied for bailable and non-bailable offences. The Court Observations study suggested that an accused is 24 times more likely to secure bail in a bailable case as opposed to a non-bailable case.

6.17

The Court Records data shows that an accused was only 7 times more likely (Figure aa). However, the overwhelming preference for judicial custody over bail, in non-bailable cases, is confirmed by both the Court Records and Court Observations data as over 70% of the accused were remanded to judicial custody. So, the single most effective measure to reduce under trial detention in India would be to prune the list of non-bailable offences in Schedule – I of the CrPC and to develop binding guidance to the police to include non-bailable offences in a complaint or charge sheet only where strong prima facie evidence exists.

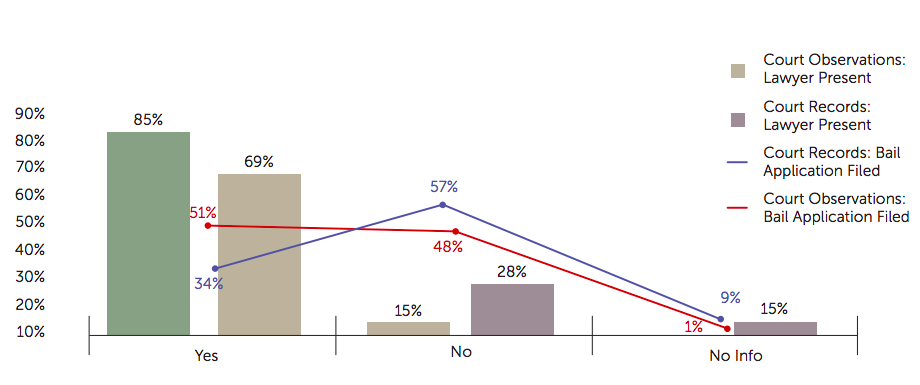

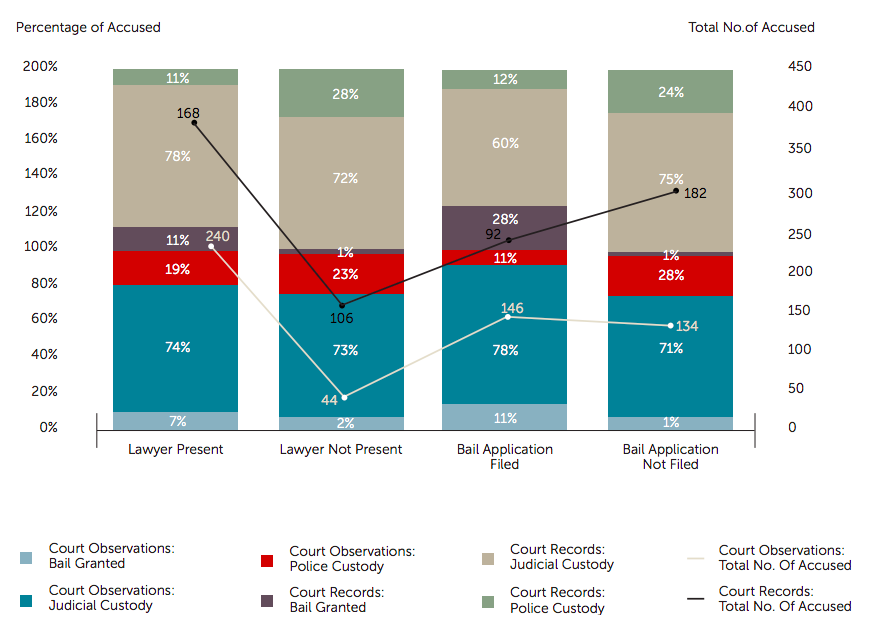

(b) Procedural Factors: Effective Legal Representation

6.18

The Court Observations data set for Bengaluru suggested high levels of legal representation i.e. 85% of the accused. In over a half of the Court Observations cases (51%), bail applications were filed on behalf of the accused.

6.19

However, the Court Records data indicated lower levels of legal representation, at about 69%, though information about legal representation for approximately 15% of the accused was unavailable. The trend continued with respect to effectiveness of legal representation, where bail applications were filed in only 34% of the Court Records cases, leaving about 56% without effective legal remedy (Figure bb). No information was available on whether bail applications were filed for about 9% of the accused.

6.20

In the Court Observations study in Chapter 5, we noted that an accused was 3 times more likely to secure bail at first production if they had legal representation and 5 times more likely to secure bail if a bail application was filed i.e. effective legal representation had a significant positive effect on bail outcomes.

6.21

This finding was confirmed by the Court Records data as well, where the availability of legal representation, and particularly effective legal representation, resulted in more orders granting bail.

An accused was 11 times more likely to secure bail if a lawyer was present and was 28 times more likely to secure bail if a bail application was filed on their behalf.

6.22

Irrespective of the availability of effective legal representation, judicial custody was the most likely outcome in both data sets, with over 70% of accused being remanded to judicial custody. In the Court Records data set, the number of judicial custody orders dropped to 60% where bail applications were filed on behalf of the accused. This was due to the significant increase in number of orders granting bail, once again confirming that effective legal representation increases the chances of receiving bail.

6.23

In the Court Records data set, the police custody orders were halved where a lawyer was present and a bail application was filed (Figure cc), except in the Court Observations study for Bengaluru. Further, while police custody orders fell by half where bail applications were filed in both data sets, the fall in police custody orders where a lawyer was present was much sharper in the Court Records data set i.e. only 11% were remanded to police custody where a lawyer was present, in comparison to the 28% who were remanded to police custody where no lawyer was present.

6.24

The precise effect of the levels of effective legal representation on bail outcomes can be measured only by controlling for the effect of other factors such as the statutory basis and nature of offences as well as the type of offence. However, the strong correlation between the presence of a lawyer and the bail decision in the Bengaluru data suggests that merely ensuring universal free legal aid for the accused can reduce under trial detention rates by about 4%.

II. BAIL IN THE PRE-TRIAL STAGE: DATA FROM COURT RECORDS IN BENGALURU

6.25

For 245 out of 274 accused in the Court Records phase, FIRs were filed with respect to all but one case. 94% of accused were arrested and the remaining 6% of accused were either untraceable or absconding (Figure dd). All those arrested were produced before the Magistrate.

6.26

Both the Court Observations and Court Records data sets show that no more than 10% of accused persons secured bail at first production, with over 70% of accused being remanded to judicial custody. However, if an accused is remanded to judicial custody or police custody at first production, they will be produced in court on subsequent occasions. Hence, bail may be sought from the trial court.

6.27

The Court Records go beyond the Court Observation data to give us a skeletal account of court proceedings up to a period of 6 months for some cases. As the Court Observations focused on the ‘first production’ as a single event of the trial, that data does not allow us to develop a wider perspective on bail decision making at other points of the criminal justice system. In this section we examine bail decisions during the pre-trial process and ask whether ‘first production’ is the primary or key stage for bail decision making in India.

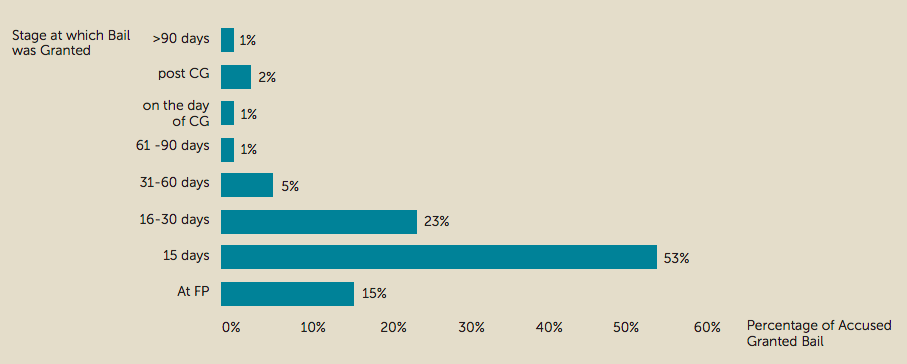

In fact, it is not at first production that bail is most often secured. More than half the accused who secured bail (53%) did so after 15 days in custody in the pre-trial stage, which may be on account of Section 167(2) of the CrPC which permits a Magistrate to remand an accused to police custody not exceeding 15 days. A further 23% were given bail after spending between 15-30 days in custody. By 30 days, nearly 95% of the accused had secured bail (Figure ee).

6.28

Out of 198 of 274 accused persons in the Court Records data set who secured bail at some point in the pre-trial stage, around 15% of accused secured bail at first production.

In fact, it is not at first production that bail is most often secured. More than half the accused who secured bail (53%) did so after 15 days in custody in the pre-trial stage, which may be on account of Section 167(2) of the CrPC which permits a Magistrate to remand an accused to police custody not exceeding 15 days. A further 23% were given bail after spending between 15-30 days in custody. By 30 days, nearly 95% of the accused had secured bail (Figure ee).

6.29

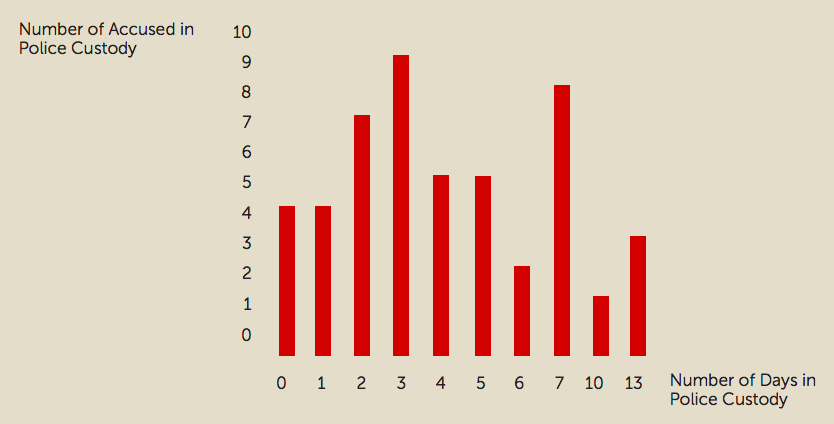

As we noted in Chapter 4, as per the CrPC, an accused may be remanded to police custody for a maximum period of 15 days whether at once or in stages. This period is subject to change depending on whether the offence committed is under the IPC or an SLL. In the Court Records data set, 48 accused were remanded to police custody, half of whom spent less than 3 days in police custody. Around three quarters of the accused spent less than 7 days in police custody. Only 3 accused were remanded to the 13 days of police custody, which was the longest period ordered in these set of cases (Fig ff).

6.30

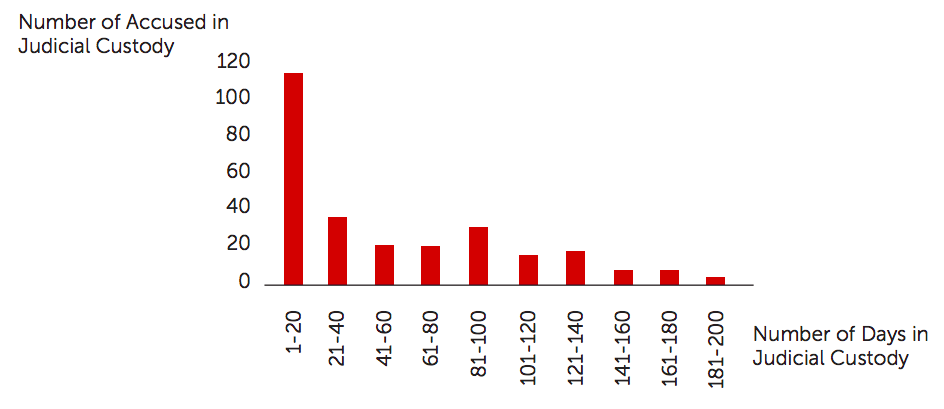

Out of the 274 accused in the courts records data set, 210 accused spent time in judicial custody and more than the half of the accused were released within 20 days. Pre-trial detention longer than 100 days was ordered in only 10% of the cases while only 1 accused was detained in judicial custody beyond 6 months. About 20% of accused persons were held in judicial custody for more than 60 days. This may be explained by the high number of non-bailable offences, which are more serious in nature, captured in the first production data set. As we may recall from Chapter 4, the maximum period for which an accused may be remanded to judicial custody, as per the CrPC, is 60 days or 90 days depending on the offence committed. Under some SLLs, this period has been extended to 180 days.

6.31

A little more than half of the accused who secured bail in the pre-trial stage did so from the court in which they were first produced though not at first production. Around 40% of the accused had to approach the Sessions Court to secure bail. Only 1% of the accused approached the High Court to obtain bail in the pre-trial stage, which also includes those seeking anticipatory bail. The 2% of accused persons who secured police bail are not relevant to this study as the data sets primarily comprise of non-bailable cases.

III. RANGE OF PUNISHMENT AND BAIL OUTCOMES

6.32

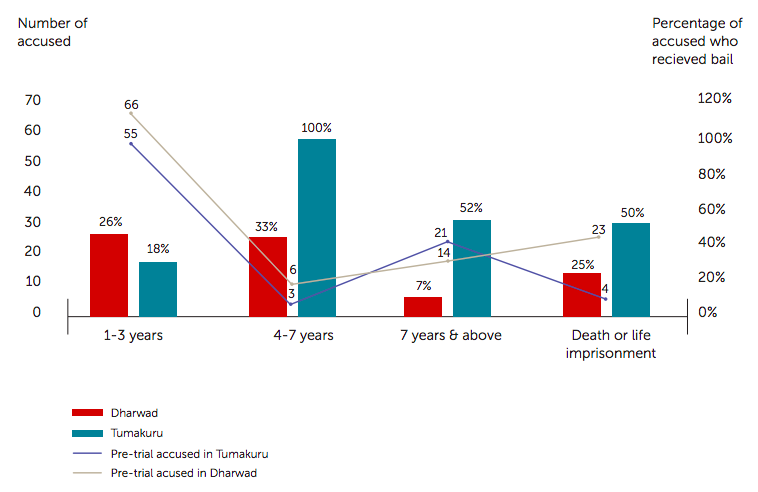

The Court Records data set presented information on the potential influence of an additional factor i.e. range of punishment, on bail outcomes. Offences may be broadly classified into four categories based on punishment prescribed – death or life imprisonment, imprisonment of 7 years and above, imprisonment of 4-7 years and imprisonment of 1-3 years. In this section we explore whether the range of punishment has any effect on the period of under trial detention. We analyse the influence of range of punishment on bail decision making in 244 cases from the Court Records data set of Bengaluru.

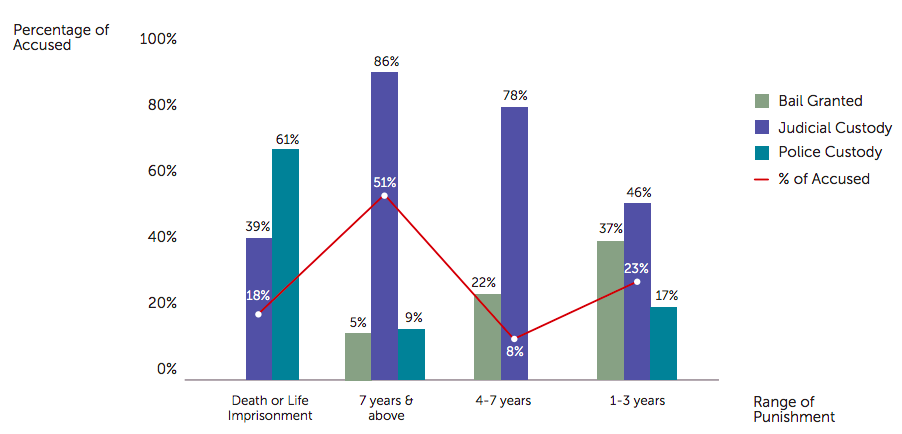

6.33

Let us begin by categorising the accused by range of punishment. Almost 18% persons were accused of offences punishable with death or life imprisonment (Figure ii). A majority of the accused (70%) were arrested for rather serious offences, punishable with imprisonment of 7 years and above, life imprisonment or death. About 23% were accused

of offences punishable with imprisonment of 1 to 3 years. This is significant as, in general, offences punishable with imprisonment of 3 years and above are also likely to be classified as non-bailable offences under Schedule – I of the CrPC. In case of such ‘serious’ offences, courts may be more restrained in granting bail.

6.34

In our study we found that at the stage of first production, a higher sentence seemed to result in a lower chance of securing bail. No person accused of an offence punishable with death penalty or life imprisonment secured bail. Only 5% of those accused of an offence punishable with imprisonment of 7 years and above secured bail. Orders granting bail increased to 22% and 37% as the range of punishment decreased from 4 to 7 years and 1 to 3 years respectively.

6.35

Judicial custody was the most common outcome except in cases punishable with death or life imprisonment where 61% were remanded to police custody at first production (Figure jj). While the high proportion of police custody orders in cases of offences punishable with death or life imprisonment is expected, the proportion of police custody orders was high at 17% for less serious offences punishable with imprisonment between 1 to 3 years. On the other hand, no police custody orders were made for offences punishable with imprisonment of 4 to 7 years in the Court Records data set. This uneven distribution at the two ends of the ranges of punishment suggests an egregious use of police power in less serious offences.

6.36

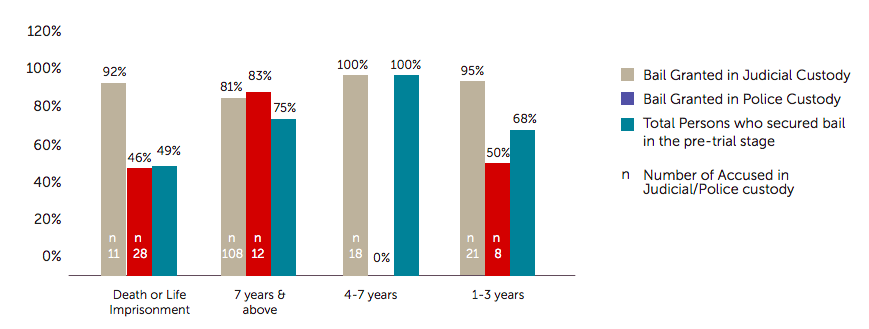

Having examined how bail decision making is influenced by the seriousness of the offence using the range of punishment prescribed for it, now we turn to the relationship between range of punishment and bail outcomes at other stages of the criminal justice process.

6.37

Ultimately, bail was also more frequently granted at a subsequent point in the pre-trial stage to accused persons who were remanded to judicial custody at first production, irrespective of the range of punishment i.e. an outcome of remand to police custody at first production disproportionately affects the chances of securing bail in the pre-trial stage for offences punishable with death or life imprisonment and offences punishable with imprisonment of 1 to 3 years.

6.38

Bail was granted only to 45-50% of persons remanded to police custody at first production, whether they were accused of offences punishable with death or life imprisonment or of less serious crimes (Figure jj). However, 83% remanded to police custody eventually received bail where they were accused of offences punishable with imprisonment of 7 years and above.

6.39

Therefore, in this section, we observed that the findings on bail decision making from the Court Observations and Court Records data sets for Bengaluru broadly confirm each other.

Most accused receive bail at some point in the pre-trial stage, with bail rates being higher at different stages (after first production) of the criminal justice process.

As in the Court Observations study, bail decisions were noted to be influenced significantly by substantive factors such as the statutory basis and the nature of the offence as well as by the levels of effective legal representation available. In the next section, we analyse bail decision making in the pretrial stage in Tumakuru and Dharwad and the extent of influence of these factors.

where an accused was held in judicial custody and police custody

B. Bail Decision Making in the Pre-Trial Stage: Dharwad and Tumakuru

6.40

In the previous section we analysed court records for first production cases in Bengaluru courts. However, as the court registry in Dharwad and Tumakuru did not maintain a register of first productions, we analysed a representative sample of all criminal cases in these two districts. So, the court records data from Dharwad and Tumakuru are not fully comparable with the data from Bengaluru. However, the data sets give us a fuller view of the pre-trial stage rather than just first productions and are useful to obtain a broader understanding of the criminal justice process.

6.41

As fewer arrests were made in Dharwad and Tumakuru, this resulted in fewer first productions in the Court Records data. In particular, a significant number of petty cases were registered under special statutes where no arrests were made or where order sheets were unavailable or incomplete.[3] As this resulted in a smaller sample size, it affects the breadth of the claims made in this section. With the limited data procured, in this section, we first analyse the court records from Dharwad and Tumakuru to identify trends in arrest and police bail rates in the two districts. Next, we focus on ‘first production’ to assess the influence of factors such as the statutory basis and nature of offence, on bail outcomes. Finally, we study bail decision making in the pre-trial stage where we go beyond the offences to understand the role of other substantive and procedural factors on bail decision making.

I. ARRESTS AND POLICE BAIL

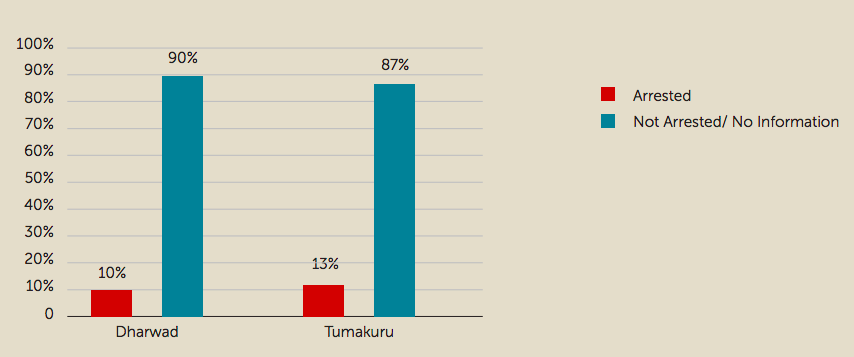

6.42

Of the 111 cases in Dharwad and 98 cases in Tumakuru analysed, only about 10% and 13% of the accused were arrested in Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively (Figure kk). All persons who were arrested in the two districts were produced before the Magistrate.[4] It may be noted here that as the Bengaluru data set did not include all court cases before the courts, we are unaware of the rate at which accused persons were arrested in Bengaluru.

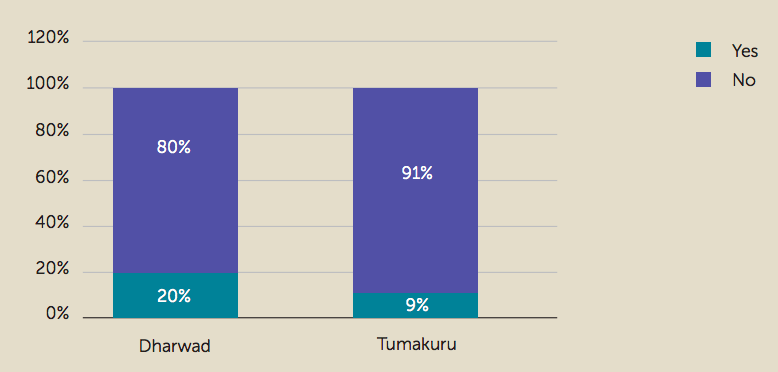

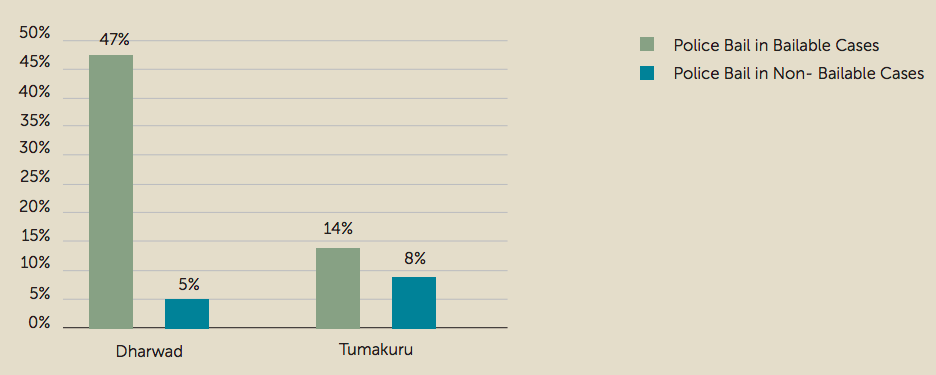

6.43

Out of the total FIRs filed 28% of the cases in Tumakuru and 34% of the cases in Dharwad were bailable.

6.44

As we noted in Chapter 4, when a person is arrested for a bailable offence, bail may be granted to an accused at the police station.

Of all the 111 and 98 cases in Dharwad and Tumakuru, we noted that 20% of accused in Dharwad and only 9% of accused in Tumakuru received police bail. Police bail was granted in almost half the bailable cases in Dharwad, while the rate of police bail was significantly lesser in Tumakuru (Figure mm). Police bail was also granted in 5% and 8% of the non-bailable cases in Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively.

6.45

With respect to bailable offences, it appears that a Dharwad police station is three times as likely to grant police bail than a Tumakuru police station. This may be due to various factors such as the offence, the accused persons’ character or a sharp divergence in police culture. Given the small sample of cases, we are unable to explain this stark variation completely.

II. BAIL DECISION MAKING AT FIRST PRODUCTION

6.46

The date of first production and related details were available only for 11 accused in Dharwad and 15 accused in Tumakuru. Therefore, our analysis of bail outcomes at first production is limited to these cases.

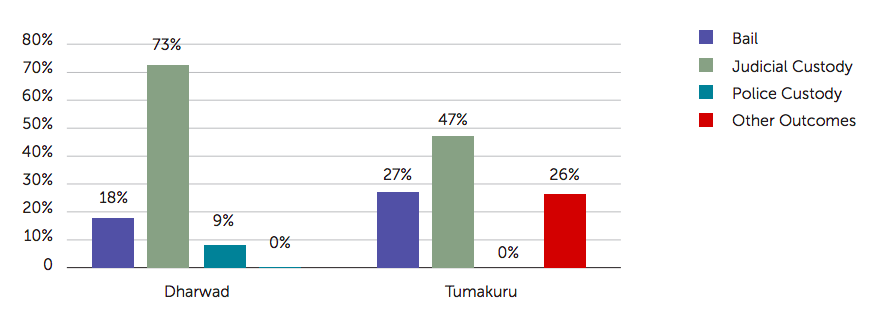

6.47

Bail was granted to 18% of the accused in Dharwad and 27% of the accused in Tumakuru. The Court Records data for Dharwad shows significant variations from our previous observations in the Court Observations study, where 26% of the accused received bail at first production. In Tumakuru, however, the rate of bail observed in the Court Records study was similar to the Court Observations study (25%).

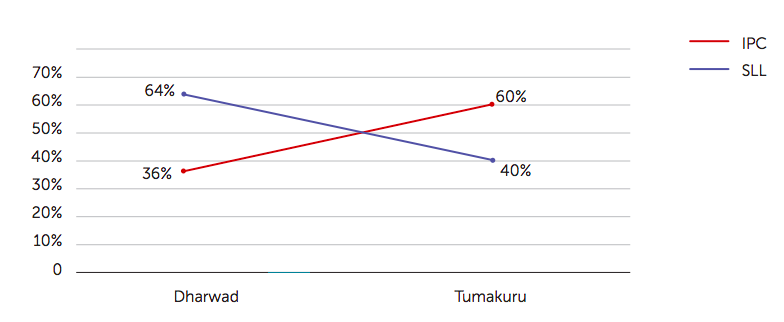

6.48

These variations in first production outcomes in the two districts may be explained by the statutory basis of offences and the type of offences before each court. Recall that in Chapter 5, we had noted that bail is more likely to be granted at first production for bailable offences and IPC offences, which was also confirmed by the findings in both districts. In the Court Records study, all the first production cases in Dharwad were non-bailable, with a majority registered under SLLs, which may explain the lower rate of bail. However, in Tumakuru, the first production cases were all bailable and a majority were registered under the IPC.

6.49

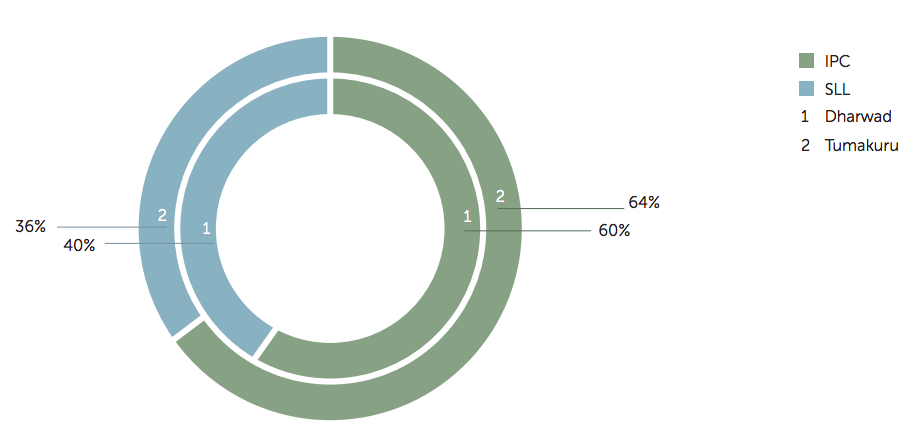

The composition of first production cases on the basis of statutory origin presented different results in Dharwad and Tumakuru. It is relevant to note here that as all persons who were arrested were

produced before the Magistrate, the composition of first production cases also tells us the rate of arrest for IPC and SLL offences.

6.50

Only about 36% of the cases in Dharwad were registered under the IPC, while in Tumakuru, 60% were IPC cases. Unlike Dharwad, the composition of cases registered under IPC and SLL in Tumakuru aligned with the numbers observed in the Court Observations study in Chapter 5.

6.51

Among the three principal outcomes at first production, judicial custody remained the most likely outcome at first production. 73% accused in Dharwad and 47% in Tumakuru were remanded to judicial custody.

Significantly, almost 71% of persons in Tumakuru who were remanded to judicial custody were accused of non-bailable cases (Figure nn).

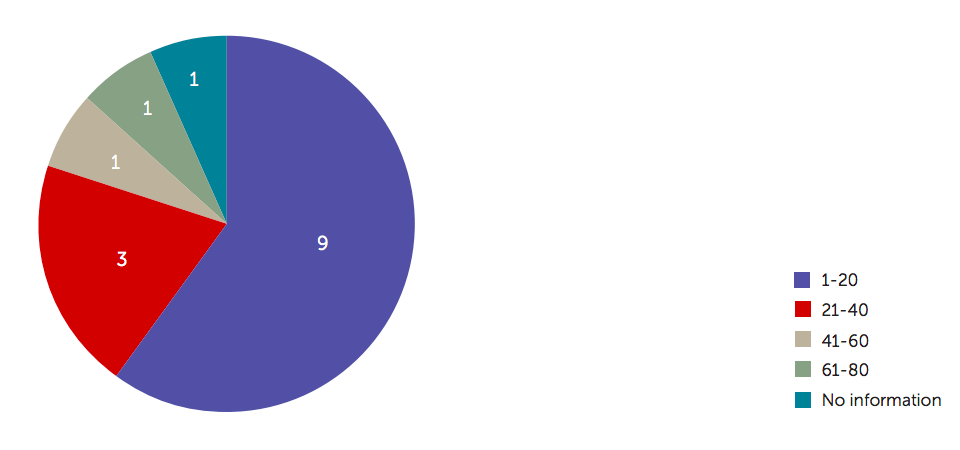

6.52

From Figure pp, we note that courts were most likely to remand an accused to less than 20 days of judicial custody at first production, similar to courts in Bengaluru. Notably, 8 of these 9 judicial custody orders were made in Dharwad. The 3 orders remanding an accused to more than 20 days of judicial custody were made in Tumakuru. This may be explained by the fact that all the 3 cases were cognizable and non-bailable offences, which as we noted in Chapter 4 are considered ‘more serious’ in nature under the scheme of the CrPC.

6.53

Finally, orders remanding an accused to police custody were negligible in both districts, with 9% of arrested persons in Dharwad and no arrested person in Tumakuru being remanded to police custody. This is similar to the numbers we noted in our Court Observations study, where only 2% accused in Dharwad and 10% accused in Tumakuru were remanded to police custody at first production.

6.54

In our Court Observations study, we found a negligible number of outcomes at first production apart from bail, judicial custody and police custody, across the three districts. However, in the Court Records study in Tumakuru, we found some other outcomes at first production such as where an accused took a ‘guilty plea’ in petty cases, punishable with fine of Rs. 100 (Figure nn). This is similar to the Court Records study in Bengaluru where about 10% of the cases resulted in other outcomes such as guilty pleas and compounding.

6.55

Having looked at bail decision making at the stage of first productions in Dharwad and Tumakuru, in the next section, we turn to bail decision making in the pre-trial stage to determine whether bail is actually most likely to be secured at first production and to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that lead to positive bail orders in the pre-trial stage.

III. BAIL DECISION MAKING IN THE PRE-TRIAL STAGE

6.56

We began this part of the Chapter analysing court records procured from Dharwad and Tumakuru. Our sample data set included 111 and 98 cases respectively. Of the accused persons named in these cases, only 10% and 13% were arrested, respectively. Of those arrested, 20% and 9% received police bail in Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively. In the section above, we analysed the bail decision making process at the stage of first production and noted that 18% in Dharwad and 27% in Tumakuru received bail at this stage.

6.57

As we discussed in Chapter 4, once a charge sheet is filed the criminal justice process enters the ‘undertrial’ stage. The period from arrest till filing of the charge sheet is the ‘pre-trial’ stage and bail may be granted at various points in this phase. Bail may be secured from the police soon after arrest, or at first production at the court of first instance. Bail may also be granted by other institutions such as the Sessions Court and the High Court at various points in the pre-trial stage. Therefore, in this section we go beyond first production and focus our attention on bail decision making across the pre-trial stage to develop a bigger picture of bail decision making.

(a) Bail in the Pre-trial Stage

6.58

In our study of the pre-trial stage, we excluded all cases where we definitively knew that no arrests had been made. The pre-trial cases include cases where police bail was granted, first production cases and cases where charge sheets were filed. However, for our study, we only considered those cases where bail was granted prior to filing of the charge sheet. Therefore, at the pre- trial stage, we analysed:

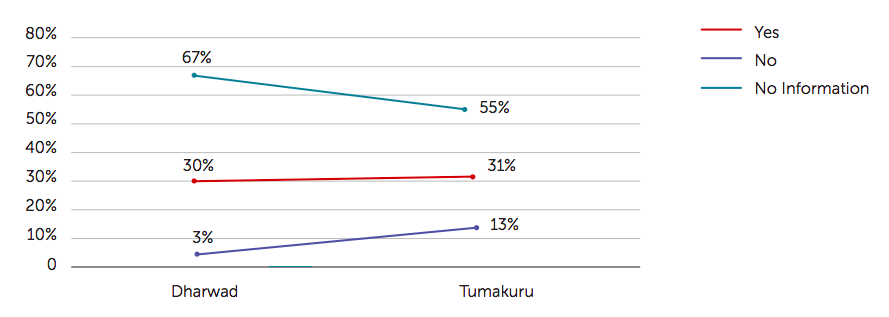

6.59

No information was available on whether the arrested person secured bail in a significant number of these cases as the order sheets were unclear. Bail rates increased in the pre-trial stage in both districts, where 30% and 31% of arrested persons received bail in Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively.

(b) Institution Granting Bail

6.60

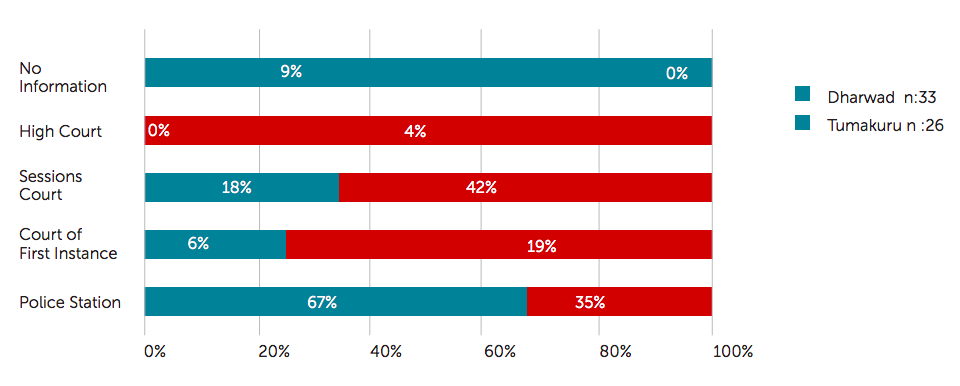

Given the significant rise in bail orders in the pretrial stage, we also analysed the various institutions which granted bail to arrested persons.

6.61

Figure rr below shows us the overall picture for pre-trial bail in Dharwad and Tumakuru with respect to the institutions that granted bail. We note that in both districts, the police station and Sessions Court are the major sites of bail decision making in the criminal justice system.

Given that only 18% accused in Dharwad and 27% of accused in Tumakuru secured bail at first production, there appears to be no special reason why first production should be considered the primary site for access to justice intervention.

6.62

In Tumakuru, 19% arrested persons secured bail in the pre-trial stage at the court of first instance, while in Dharwad, only 6% arrested persons secured bail from that court.

As we noted earlier, a significant number of arrested persons secured bail from the police station, even where they were accused of committing non-bailable offences. In fact, the number of arrested persons who secured bail from the police station in Dharwad was almost double that of Tumakuru.

In addition to this, appellate courts such as the Sessions Court also granted bail to 18% and 42% of arrested persons in Dharwad and Tumakuru.

c) Statutory Basis and Nature of Offences

6.63

Unlike the first productions data set for Dharwad and Tumakuru, the composition of cases based on statutory origin of the offence were similar in the both pre-trial data sets i.e. 60% IPC cases and 40% SLL cases. Out of the IPC cases, in both districts, offences against the body were the most common, followed by offences against property.

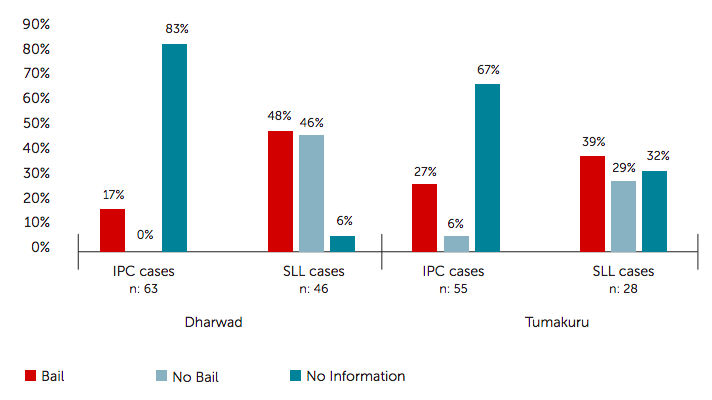

6.64

In the Court Observations study in Chapter 5, we found that across the three districts, the rate of bail was higher for IPC offences than SLL offences. However, the most surprising result from the Court Records data set was that bail was granted more frequently for SLL offences in both districts. In Tumakuru, 27% IPC cases received bail compared to 39% of the SLL cases. In Dharwad, the difference was significant, as bail was granted in 48% of SLL cases compared to just 17% of IPC cases (Figure tt).

6.65

A substantial number of ‘other offences’ were observed in both districts. In Dharwad, these were a combination of offences against the body and State (30) while in Tumakuru, they were a combination of offences against the body and property (20). These ‘other offences’ were included in the overall numbers of offences against the body.

6.66

No clear trend was evident from the bail outcomes based on the nature of the offence. Significantly, 20% cases that were categorised as offences against the body were granted bail in Dharwad while no cases of offences against property were granted bail. As we noted in Chapter 5 in the Court Observations study of Bengaluru, bail was granted least for offences against property.

6.67

Offences against body and offences against property received bail at the same rate in Tumakuru (27%). It is pertinent to once again note that the category of ‘offences against body’ includes ‘other offences’ as well, which may explain the higher rate of bail for offences against the body in both districts. Only

The most surprising result from the Court Records data set was that bail was granted more frequently for SLL offences in both districts. In Dharwad, the difference between bail granted for IPC and SLL cases was significant. Bail was granted in 48% of SLL cases compared to just 17% of IPC cases (Figure tt).

one offence against the State was observed in the overall data pool, which was from Dharwad, and the arrested person was granted bail (Figure uu).

(d) Range of Punishment

6.68

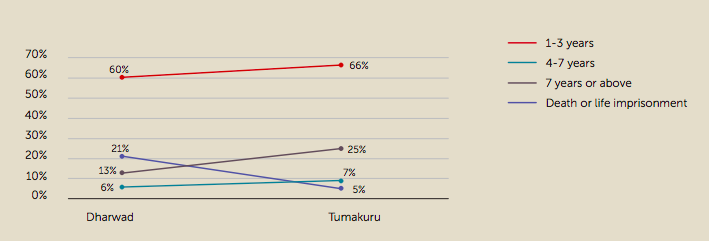

The final substantive factor shaping bail outcomes that we measured is the range of punishment prescribed for the offence. Over 50% of the accused in Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively were accused of offences punishable with imprisonment between 1-3 years. On other punishment parameters, there was some variation amongst the districts. In Dharwad, almost 21% were accused for offences involving death or life imprisonment. However, in Tumakuru, only 5% were accused of this category of offences while a higher 25% were accused of offences with imprisonment of 7 years and above (Figure mm).

6.69

Earlier in this Chapter, in the context of pre-trial bail decision making in Bengaluru, we showed that the range of punishment was inversely proportional to the likelihood of securing bail. We tested it in Dharwad and Tumakuru as well, and observed the variations in bail outcomes based on the range of punishment prescribed for the offence.

6.70

Overall, bail was frequently granted for offences punishable with imprisonment of 1-3 years in both districts. For offences of all types except punishable with imprisonment of 1-3 years, bail was more likely to be granted in Tumakuru than Dharwad. As expected, in both districts the rate of bail was high for offences where no more than 7 years was of punishment has been prescribed as the punishment.

6.71

Surprisingly, in Tumakuru, offences that are considered ‘more serious’ on account of higher ranges of punishment i.e. imprisonment of 7 years and above, life imprisonment and death penalty, received bail frequently. Those accused of the most serious offences which permitted death or life imprisonment received bail at significantly higher rates in Tumakuru than those accused of lesser offences in Dharwad. However, as the number of accused is very small, this may be a statistical outlier to be ignored. Therefore, from this dataset, we were unable to establish any clear linear relationship between range of punishment and pre-trial bail outcomes.

6.72

While we have analysed the effect of various substantive factors on bail outcomes in the pre-trial stage in Dharwad and Tumakuru, we were unable to do so with the procedural factors. In Chapter 5, we had analysed the impact of legal representation and other due process factors on bail outcomes at first production in the three districts. We also carried out a similar, but limited analysis in the Court Records study in Bengaluru. Through this, we learnt that the presence of effective legal representation has a positive influence on bail decision making, thereby increasing the likelihood of bail.

(e) Legal Representation

6.73

However, in the Court Records study in Dharwad and Tumakuru, due to the poor record keeping practices, information on legal representation and compliance with due process factors was unavailable in more than 90% of the cases. Consequently, the relationship between legal representation and bail outcomes could not be clearly observed. Further, there was insufficient information on the presence of effective legal representation such as whether bail applications were filed on behalf of accused persons. Where information was recorded, the arrested persons were not legally represented in no more than 30% cases in both districts, which aligns with the findings from the Court Observations study in Chapter 5.

We found that substantive factors like statutory basis and nature of offences, the classification of offences into bailable and non-bailable and range of punishment are crucial to bail decision making at all stages of the criminal justice process. Therefore, the formal and informal classification of offences as ‘serious’ and ‘non-serious’ based on the above must be urgently revisited to ensure that bail is granted early on in the pre-trial stage and further, that persons accused of such offences do not form part of the flow of under-trial prisoners.

Conclusion

6.74

We undertook the Court Records study as a second data source to verify and validate the Court Observations data. The Court Records study in Bengaluru, Dharwad and Tumakuru largely confirm the findings of the Court Observations study. While the Bengaluru Court Observations and Court Records data sets show greater correspondence with each other, in Dharwad and Tumakuru, correspondence could not be easily established due to inadequate information in a significant number of cases. In Dharwad and Tumakuru, the difficulty in identifying trends in bail decision making and measuring the influence of various substantive and procedural factors may be attributed to the disorganised system of maintaining court records in the Magistrate courts in Karnataka. This suggests that a protocol for recording information is required in the lower courts to ensure informed decision making that is consistent and uniform across districts.

6.75

The finding across the three districts is that while bail is secured in the pre-trial stage, it is not always secured at first production. Further, the most commonly ordered duration of detention was between 1 to 20 days, where the court awarded judicial custody at first production. While such similarities between the three districts were observed, the differences in police, prosecutorial and judicial cultures were inescapable. For instance, unlike Bengaluru, the rate of bail for SLL offences was higher than for IPC offences in Dharwad and Tumakuru. These differences may have a bearing on the approach to arrests and bail decision making, whether at the police station or the courts.

6.76

Similar to the Court Observations study, SLL offences were numerous and common in both districts. Further, most cases involved charges which are a combination of offences against property, body and the State, also known as ‘other’ offences. As they dominate the cases before the court, police practices in recording cases need to be studied more carefully to explain this. Finally, in both districts, a majority of cases involved offences punishable with imprisonment of less than 3 years or ‘less serious’ offences, though the limited data did not permit us to arrive at any clear finding on the impact of range of punishment as a factor on bail decisions. Surprisingly, and unlike Bengaluru, bail was granted frequently for offences punishable with death and life imprisonment.

6.77

The effectiveness of legal representation in ensuring bail could be tested only from the Court Records data for Bengaluru as information for Dharwad and Tumakuru was unavailable in most of the cases. The data from Bengaluru confirmed our findings from the Court Observations study that effective legal representation undoubtedly has a positive effect on bail.

6.78

In conclusion, we found that substantive factors like statutory basis and nature of offences, the classification of offences into bailable and non-bailable and range of punishment are crucial to bail decision making at all stages of the criminal justice process. Therefore, the formal and informal classification of offences as ‘serious’ and ‘non-serious’ based on the above must be urgently revisited to ensure that bail is granted early on in the pre-trial stage and further, that persons accused of such offences do not form part of the flow of under-trial prisoners.

References

- In Bengaluru, we analysed 240 IPC cases and 44 SLL cases in the Court Observations data set and 202 IPC cases and 43 SLL cases in the Court Records data set ↵

- In Bengaluru, we analysed 23 bailable cases and 260 non-bailable cases in the Court Observations data set and 12 bailable cases and 233 non-bailable cases in the Court Records data set ↵

- 21% and 28% persons in Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively were accused of offences under special statutes such as the Electricity Act, 2003, Karnataka Excise Act, 1966, Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 read with the Karnataka Minor Mineral Concession Rules, 1994 and Karnataka Police Act, 1963 ↵

- In Dharwad and Tumakuru, court records reveal only the gender of the accused, among various other social and demographic indicators. Even gender was not recorded in over 10% of the cases in Dharwad. However, the data from both Dharwad (3.6%) and Tumakuru (6.4%) align i.e. only about 5% of the accused in the courts were women. ↵