4.1

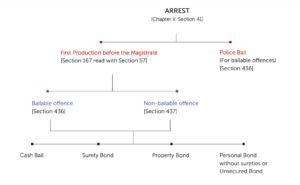

In India, any person may be arrested by an investigating authority on a reasonable suspicion that an offence has been committed. Such a detenue may secure a conditional release – bail – from the relevant authority. If the offence is categorised as a ‘bailable’ offence, the detainee may secure bail at the police station. However, if the offence is categorised as a non-bailable offence, the detenue must seek bail from the appropriate court.

4.2

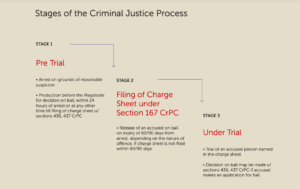

In this background, we outline the law applicable to arrest and grant of bail. We introduce the distinction between the ‘pre-trial’ and ‘under-trial’ stages of the criminal process – one that has not been made in the substantive law, academic analysis or policy literature in India. We argue that this distinction is essential in identifying relevant factors to be considered while making a bail decision and the appropriate weights to be attached to them at different stages of the criminal justice process. Next, we present an outline of the law applicable at the pre-trial and under-trial stages of the criminal justice process and briefly review the theoretical considerations that shape this area of law as well as the recent efforts of the Supreme Court at reform. The Chapter concludes with a review of the latest attempts to reduce under-trial detention rates in India and highlights how existing law has failed to substantively regulate bail decision making in courts.

A. Legal Framework of Arrest and Bail

4.3

Under Section 41, the investigating authorities may arrest a person on a reasonable suspicion that an offence has been committed, whether bailable or non-bailable. The provisions applicable to a bail decision differ based on whether an offence is classified as bailable or non-bailable in Schedule – I of the CrPC.

While the power of courts and police to grant bail in case of a non-bailable offence is discretionary,[1] a person arrested for a bailable offence has a right to be released on bail by the police. This may take place within 24 hours from the time of arrest. Where an arrested person has been refused police bail for a bailable offence, they may approach the court to secure bail.[2]

4.4

Every arrested person must be produced in court within a period of 24 hours of arrest, which is commonly known as ‘first production’.[3] At first production, the court decides whether to release the arrested person on bail or remand them to judicial or police custody.

Although the judiciary has been largely silent[4] on the arbitrariness of the classification of bailable and nonbailable offences, several legal reform efforts have attempted to confront the issue:

• The Expert Committee on Legal Aid (1973) headed by Justice Krishna Iyer recommended enlarging the category of bailable offences in the CrPC to facilitate grant of bail in a greater number of offences and to ensure expeditious completion of pre-trial procedures.

• In its 154th Report (1996), the Law Commission of India reviewed the law on arrest and supported the finding of the National Police Commission that a substantial number of arrests were made in cases of minor offences and were not necessary for crime control.[5]

• The Malimath Committee on Reforms of the Criminal Justice System (2003) recommended a complete overhaul of the criminal justice system, including reclassifying offences into separate codes.[6] Significantly, the Committee referred to specific factors such as nature of the crime, degree of violence, injury to victim/property, societal impact, and the possibility of using alternative dispute resolution methods to determine whether an offence ought to be classified as bailable or nonbailable and cognizable or non-cognizable.[7]

• Recently in its 268th Report, the Law Commission of India (2017) also emphasized the need to rationalize the classification of offences and recommended that the seriousness of the offence must reflect in its classification as bailable or nonbailable.[8]

4.5

An order of remand to police custody results in detention of the accused in the police station or any other facility controlled by them. Under the CrPC, the criminal court may remand an accused to police custody for a maximum period of 15 days, whether at once or for multiple smaller periods of time.

4.6

Where an order of remand to judicial custody is made, the accused is transferred to the local jail administered by the department of prisons. Judicial custody may be ordered for a maximum period of 60 or 90 days depending on the nature of the offence, subsequent to which the accused person has a right to be released on bail[9] irrespective of whether the police has filed a ‘charge sheet’.[10]

4.7

If the accused is remanded to judicial or police custody, bail hearings may take place at multiple points in the criminal process i.e. each time the accused is produced before the court.

4.8

The bail decision is regulated by Sections 436-439 of the CrPC. Section 436 provides that a person arrested or detained for a bailable offence must be released on bail if they are prepared to furnish bail[11] while Section 437 applies only to non-bailable offences. Any person who believes that they may be arrested on the suspicion of having committed a non-bailable offence may apply for anticipatory bail under Section 438, CrPC, to the High Court or Sessions Court. The substantive provision on bail discussed above apply at all stages of the criminal justice process. However, it is analytically significant to distinguish between the pre-trial and undertrial stages as the same considerations may bear different weights in bail decision making in each stage.

4.9

The period from arrest till filing of charge sheet may be termed as the ‘pre-trial’ stage, where the police are operating merely on a suspicion that the person arrested has committed an offence. Filing of the charge sheet indicates that the investigation phase of the criminal justice process has been completed and the investigating officer is convinced that there is sufficient evidence to support a successful prosecution. The ‘under trial’ phase commences after a charge sheet is filed and continues until the completion of the trial and pronouncement of the judgment.

4.10

In the rest of this Chapter, we use this distinction to organise the analysis of the statutory provisions that shape a bail decision at each stage. We explore judicial interpretation of these statutory provisions, to highlight how courts have guided the discretion of lower courts in bail decisions.

I. PRE – TRIAL STAGE

(a) Arrest

4.11

We had noted earlier that an investigating officer has the power to arrest any person under Section 41 of the CrPC. Offences are further classified into ‘cognisable’ and ‘non-cognisable’ offences and this determines the procedure to be followed in each case. A police officer, either on receiving information or independently coming to know of the commission of an offence, must first determine whether the offence is cognisable or noncognisable.

4.12

The power to arrest varies greatly depending on whether an offence is categorized as cognisable and non-cognisable. An officer in charge of a police station may arrest a person without a warrant in case of cognizable offences[12] and is empowered to commence investigation and make arrests without the order of a Magistrate.[13]

4.13

However, where a non-cognizable offence is committed, the police cannot make an arrest[14] without a warrant of arrest from a Magistrate. The officer in charge of the police station must note down details of the offence and refer the informant to a Magistrate.[15] The police can exercise their powers of investigation only upon an order for investigation being passed.[16]

4.14

The Supreme Court’s directions in landmark cases such as Sheela Barse,[17] D.K. Basu,[18] and recently, in Arnesh Kumar[19] have further restricted arbitrary police power with regard to arrest, by requiring the police officer to (i) inform the person of the grounds for their arrest, and their right to apply for bail upon arrest,[20] (ii) intimate the legal aid committee of the arrest, (iii) inform a relative or friend about the arrest,[21] (iv) prepare a memo of arrest containing the date and time of arrest, which is to be attested by at least one witness and countersigned by the arrested person,[22] and (v) arrange for a medical examination of the person arrested, to be conducted by a trained doctor for every 48 hours in custody.[23]

4.15

In 2009, the guidelines of the Supreme Court in Joginder Kumar v. State of Uttar Pradesh[24] were codified as an amendment to Section 41 of the CrPC, 1973. The amended provision places limitations on the power to arrest in cases of cognizable offences for which imprisonment of 7 years or less has been prescribed as punishment[25] by requiring a police officer to record the reasons for a decision on arrest, in writing.[26]

4.16

Further, amendments to the CrPC[27] have limited the police’s power of arrest and reiterated the various guidelines of the Supreme Court.[28] In particular, Section 41A was introduced as an alternative to arrest to ensure that a person who is not arrested is available for investigation. It permits a police officer to issue notice to such person, requiring them to appear at a specified place. If the person does not comply with the terms of the notice or is unwilling to be identified, the police officer may arrest such person for the offence mentioned in the notice.[29]

4.17

Section 41B requires that the police officer must bear an accurate, visible and clear identification of the accused person’s name to facilitate easy identification, prepare a memorandum of arrest which is attested by at least one witness and countersigned by the person arrested, and inform the person arrested that he has a right to have a relative or a friend named by him to be informed of his arrest. Further, the newly introduced Section 41C mandates the establishment of control rooms in every district and in every State to compile the list of all persons arrested along with relevant details. Upon arrest, the person has the right to meet an advocate of their choice during interrogation by the police under Section 41D. However, despite these reforms, the overall number of arrests in India has not seen a substantial reduction. Now we turn to assess the legal regulation of police bail in India, upon arrest.

(b) Police Bail For Bailable Offences

4.18

A person arrested for a bailable offence has a right to bail under Section 436. Within the first 24 hours of arrest, the arrested person is entitled to secure bail at the police station. The arresting officer is required to inform the person of this right so that the person may furnish bail or arrange for sureties.[30] The police officer must release a person who has signed their bail bond[31] and the requirement to furnish surety may be done away with if the officer sees fit.[32] Significantly, an indigent person is required to be granted bail without the requirement of a surety.[33]

(c) First Production

4.19

Once a person is arrested and detained in custody, whether for a bailable or non-bailable offence, they must be produced before the nearest

Judicial Magistrate within a period of 24 hours,[34] along with copies of the entries made in the case diary.[35] This stage is described as the stage of ‘first production’, which is the earliest stage of intervention by the courts and is the first point at which the judiciary exercises oversight in the criminal process.

At first production, the Magistrate may grant (i) bail under Section 436 (bailable offence) or Section 437 (non-bailable offence) (ii) authorise the detention of the accused in police custody for a maximum of 15 days or (iii) remand the accused to judicial custody.[36]

4.20

While courts initially took an unnaturally broad view on ‘first production’ by permitting detention even when accused persons were not physically produced,[37] over time, the higher judiciary has restored the textual meaning of Section 167.[38] The current legal position is that a person arrested must be physically produced before a Magistrate within 24 hours of arrest.[39]

(d) Bail In Bailable Offences

4.21

Section 436 provides that a person arrested for a bailable offence has a right to secure bail. Where police bail, as discussed above, is refused to a person accused of a bailable offence, they may seek bail from court at first production. As the CrPC does not lay down a guide for bail decision making, the considerations that shape such a decision are similar, whether at the police station or in the court.

4.22

Even in the case of a bailable offences, the court may refuse to grant bail on a subsequent occasion when the person appears or is brought before court and has failed to comply with the conditions of the bail bond.[40]

(e) Bail In Non-Bailable Offences

4.23

Under Section 437 of the CrPC, the courts and police officers have the discretion to grant bail to persons accused of a non-bailable offence and the reasons for granting bail under this section must be recorded in writing.[41] Over the years, courts have identified several key factors which determine whether a person should be granted bail, which includes the nature of the allegation, severity of punishment if the accused is convicted, available evidence, danger of the accused absconding if released on bail, probability of interference with the investigation or prosecution, sex/age/health of the accused, and larger public interest.[42] Bail that is granted can be revoked and an accused person can be arrested and committed to custody.[43]

4.24

The discretion available to courts to grant bail under Section 437 is limited in several ways. First, where there are ‘reasonable grounds for believing that a person is guilty of an offence punishable with death or imprisonment for life’ then bail may be refused.[44] Second, if the person is (i) accused of a cognizable offence and was previously convicted of an offence punishable with death, imprisonment for life or imprisonment for seven years or more, or (ii) was previously convicted of a non-bailable and cognizable offence on two or more occasions, then the court must refuse bail.[45] However, these two restrictions do not apply if a person is under the age of sixteen years, is a woman, or is a sick or an infirm person.

(f) Bail After First Production

4.25

At first production, if an accused person was refused bail and was remanded to judicial or police custody, they may still seek bail at a subsequent point in the criminal process. At this stage as well, three principle outcomes are possible – bail, judicial custody or police custody i.e. when the accused is produced subsequently, either in person or through a video conferencing facility,[46] the Magistrate may either grant bail or re-order police or judicial custody of the arrested person.

4.26

Police custody may be ordered for no more than 15 days, whether at once or in multiple shorter periods of time. Alternatively, if the court decides to order judicial custody, it may do so up to 90 days for cases involving offences punishable with death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment for a period exceeding 10 years.[47] For all other cases, the maximum period of judicial custody is 60 days.[48]

4.27

On the expiry of 60 or 90 days, as applicable, and irrespective of whether a charge sheet has been filed, an accused person has a statutory right to bail, provided they are able to furnish the bail amount.[49]

(g) Bail Conditions

4.28

Under Section 437 of the CrPC, which deals with bail in case of non-bailable offences, if a person is accused or suspected of committing (i) an offence punishable with imprisonment extending to 7 years or more, (ii) an offence against the State, an offence against the human body, or an offence against property, or (iii) abetment, conspiracy or attempt to commit any of these offences, the court can impose conditions on the bail. Such conditions may be in relation to attending the scheduled hearings in the case in accordance with the bond, refraining from committing the same or a related offence while enlarged on bail and not interfering with the investigation and not tampering with the evidence[50] among others.[51] However, this list of conditions is not exhaustive, and the court has the power to impose any other condition in the interest of justice.[52]

4.29

In addition to the above, a judge making a bail decision may impose a range of financial conditions on the arrested person as set out in Sections 440 to 450.[53]

4.30

While the provisions on bail under the CrPC are applicable equally to offences under the IPC as well as SLLs, some special statutes have introduced additional conditions to the grant of bail. For instance, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 (UAPA) requires that the Public Prosecutor be given an opportunity to be heard regarding the bail application filed by a person accused of certain offences punishable under the Act. In fact, such an accused person shall not be released on bail where the court is of the opinion that a prima facie case has been made out against the accused, based on the case diary or the police report.[54] This provision was introduced despite the fact that courts are not required to go into the merits of the case while making a bail decision, particularly at early stages of investigation and first production.

4.31

Similar restrictions on granting bail are codified under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 2002 (NDPS Act), under which bail may not be granted in respect of certain offences unless the Public Prosecutor is given a hearing, and where the court is satisfied that (i) the accused is not guilty of the offence and (ii) he is not likely to commit any offence while on bail.[55] Thus, the provisions on bail under the CrPC are necessarily subject to the applicable provisions under the NDPS Act.[56] As we will see in Chapter 5, bail is granted less frequently for SLL offences, when compared to IPC offences, which may be explained by the inclusion of such additional conditions to scheme of bail decision making under the CrPC.

4.32

Significantly, the UAPA[57] and the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989[58] (PoA Act) also place a bar on the grant of anticipatory bail under Section 438, CrPC.

II. UNDER – TRIAL STAGE

4.33

Under Section 173, the officer in charge of the police station shall submit a police report (commonly known as the charge sheet) to the court on completion of investigation, making out a case against the accused person. Under Section 190, the court may accept the charge sheet and commence trial, or reject the charge sheet and discharge the accused.

4.34

While Section 167 of the CrPC provides for automatic bail of an accused person where investigation is not completed within 60 or 90 days after arrest, depending on the nature of the offence, special statutes like the UAPA and NDPS Act have considerably extended these timelines. Under both statutes, the period of completion of investigation has been specifically extended from 90 days to 180 days for certain offences, in keeping with the notion that SLL offences are more serious in nature and such statutes have been enacted to combat a particular social ill.[59] In fact, under the NDPS Act in particular, the court may even extend the time period to complete investigation to 1 year, if the Public Prosecutor submits a report providing reasons for the delay.[60]

4.35

Irrespective of the applicable law, the pre-trial or investigation phase of the criminal justice process ends once the charge sheet is filed. At this stage, the investigating authority has gathered sufficient evidence against the accused to commence trial or no evidence is forthcoming and the accused is discharged.

4.36

However, the distinction between the pre-trial and under-trial stages of the criminal justice process has not been made in the Indian context in law or in policy reform efforts, despite the fact that the considerations while deciding on continued detention or release of an accused ought to categorically differ. In the context of bail decision making, the consequence of the failure to make this distinction is that the same statutory provisions and case doctrine are applied to the bail decision at both stages. Therefore, even subsequent to filing of the charge sheet, Sections 436 to 439 continue to govern bail decision making.

4.37

On filing of the charge sheet, it is common for an accused who has not yet been released on bail to file an application for bail under Sections 436, 437 or 439. At this stage, the bail application will plead material ‘change of circumstances’[61] to support the release of the accused on bail.

4.38

Section 437 provides that if, at any time after the conclusion of the trial of a person accused of a non-bailable offence, and before judgment is delivered, the court sees reasonable grounds for believing that the accused is not guilty of the offence, it can release the accused on the execution of a bond without sureties for his appearance to hear the judgment delivered.[62] Further, where the trial of a person accused of a non-bailable offence is not complete within sixty days from the first date fixed for taking evidence, and the accused has been in custody for the entirely of that period, the court may release such accused on bail.[63]

4.39

In the event that an accused has not been released on bail through the course of trial, Section 436A imposes a statutory limit on detention where trial has not commenced. If an accused person has undergone more than half of the maximum period of imprisonment prescribed for the offence, whether during the period of investigation into, inquiry or trial of the offence, the accused must be released on his personal bond, with or without sureties.[64]

4.40

On the completion of a trial,[65] the accused is either convicted and sentenced or acquitted and set free.[66] Where a custodial sentence is imposed, the accused has the right to appeal and apply for bail during the pendency of the appeal.[67] For the purposes of this study we are not concerned with post-conviction bail decisions or with other forms of early conditional release and parole for convicted prisoners.

4.41

Thus, bail decisions at all stages of the criminal justice process are ultimately guided by four main considerations – (i) preventing the accused from absconding during the investigation and trial, (ii) preventing the commission of further crime on release, (iii) preventing tampering with evidence or intimidating witnesses and (iv) preventing public disorder that may result from releasing an accused involved in a serious crime.[68]

The stringent provisions on bail under SLLs may be correlated to the ‘public disorder’ purpose, where additional fetters have been placed on bail being granted for SLL offences which are considered to be more serious in nature.

B. Bail Decision Making and Due Process Safeguards

4.42

A decision to grant or refuse bail, like any decision in a criminal justice system,[69] is guided and influenced by dual considerations of ‘crime control’ and compliance with due process protections[70] that are constitutionally guaranteed to accused persons. As we observed in the previous section, while the procedural and bail provisions under the IPC uphold these constitutional protections, the enactment of similar yet more stringent provisions under SLLs appear to be driven by the ‘crime control’ goal.

4.43

Constitutional due process guarantees place fetters on an overbroad exercise of powers by the police and courts under the CrPC. Due process is at the heart of Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees to every person the right to life and personal liberty, except by procedure established by law. A specific codification of one such protection is Article 22(3),[71] which prohibits the detention of a person in custody beyond 24 hours without the authority of a magistrate,[72] which has also been incorporated under the CrPC.[73]

4.44

The right to procedural protections in the criminal justice process, before and during trial, have been upheld as an inalienable part of the right to free and fair trial.[74] Over the years, courts have broadened and defined the ambit of this ‘right to include several ‘substantive and procedural due process rights’, which apply equally to bail decision making. In this section, we briefly review the extent to which some of the due process rights relating to bail decision making has been shaped by court decisions.

I. RIGHT TO SPEEDY TRIAL

4.45

The Supreme Court, in A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak,[75] held that the right to speedy trial applies to all stages of a criminal proceeding, including investigation, inquiry, appeal, and revision. This right was reiterated in Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee Representing Under trial Prisoners v. Union of India and Another,[76] where the Supreme Court held that unduly long periods of under-trial incarceration violates Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. The Court directed that an accused person who has served half the maximum sentence specified for the offence of which he has been accused should be released on bail, subject to fulfilling the conditions of bail imposed on him. This standard was incorporated in the CrPC in Section 436A through an amendment in 2005.[77]

4.46

Recently, in Husain and Anr v. Union of India,[78] the Supreme Court issued directions to guide Magisterial decision making on bail and directed the High Courts to frame annual action plans for (i) fixing a tentative time limit for subordinate courts to decide criminal trials of those in custody and (ii) monitoring the implementation of such timelines periodically. The Court recommended that Magistrates should dispose of bail applications within one week. Further, High Courts were directed to ensure that bail applications before them are decided within one month and criminal appeals, where accused have been in custody for more than five years, are concluded at the earliest.

II. RIGHT TO LEGAL COUNSEL

4.47

In Mohd. Ajmal Amir Kasab v. State of Maharashtra,[79] the Supreme Court reiterated the legal position in its earlier judgments that the right to counsel, including right to free legal aid begins at the stage of first production. The Court defined the purpose behind guaranteeing this right within the pre-trial framework as an “accused would need a lawyer to resist remand to police or judicial custody and for granting of bail; to clearly explain to him the legal consequences in case he intended to make a confessional statement in terms of Section 164 CrPC; to represent him when the court examines the charge-sheet submitted by the police and decides upon the future course of proceedings and at the stage of the framing of charges”.

4.48

This right was placed on a high pedestal in Khatri (II) and Ors. v. State of Bihar and Ors.[80] by making it obligatory for the Magistrate to inform an accused person of their right to seek counsel, and if indigent, of the right to free legal aid. For an indigent and illiterate accused, the Court noted that “even this right to free legal services would be illusory…unless the Magistrate or the Sessions Judge before whom he is produced informs him of such right.” Failure of the Magistrate to discharge this duty could make them liable to disciplinary proceedings, or vest in the accused, a right to claim compensation against the State.[81]

4.49

However, despite the statutory and judicial recognition of the right to counsel even at the pre-trial stage,[82] the 268th Law Commission Report noted that access to legal aid in the pre-trial stage is often limited for accused persons as lawyers are available only after the charge sheet has been filed, and accused persons are often unable to meet the monetary conditions of bail.[83]

III. RIGHT TO BE FREE FROM HANDCUFFS

4.50

Certain rights specific to production of the accused before the court have been recognised, such as the right against handcuffing and right to be heard by the judge. In Prem Shankar Shukla v. Delhi Administration,[84] ‘handcuffing’ by the police was held to be in violation of the constitutional scheme of Articles 14, 19, and 21. The Supreme Court severely curtailed the use of handcuffs and other fetters on the under-trial accused by the police to exceptional cases and only with permission of the Magistrate, making handcuffing of an accused the exception and not the norm. Therefore, when a person is arrested without a warrant, use of handcuffs is permissible in exceptional cases and only till he is produced before the Magistrate. Thereafter, handcuffs may only be used with the court’s permission.[85]

IV. RIGHT TO BE HEARD

4.51

The right of the accused to be heard implies a positive duty on courts to ensure that the accused person is given a full and fair hearing in each case and the matter is given sufficient and due consideration, in keeping with the principles of natural justice. Therefore, even at the stage of first production and during bail hearings, the court is required to hear the accused person.

V. CONDITIONS OF DETENTION

4.52

The conditions of detention in prisons has captured the imagination of the Supreme Court right from the Sunil Batra decisions[86] since which it has time and again issued various directions to monitor and improve the conditions in jails. Yet, overcrowding and hygiene issues remain a persistent feature of Indian prisons.[87] In this section, we look at laws applicable to conditions of detention in Karnataka as well as policy efforts and decisions of the Supreme Court that have attempted to address this issue.

Timely presentation of the accused before the magistrate is crucial for the case to progress and avoid unnecessary and prolonged confinement. However, in Karnataka, it was found that between September 2014 and February 2015, a monthly average of 2,490 under-trial accused were not produced in court due to shortage of police escorts.132 For every 100 police escorts requested, only 70 were sent for production of the accused.133

Model Prison Manual

In 1972, a Working Group on Prisons emphasized the need to have a national policy on prisons.[88]

This was also echoed by the All India Committee on Jail Reforms (1980-83) headed by Justice A.N. Mulla[89] which made several recommendations for the benefit of under-trial prisoners, such as confinement in separate institutions,[90] amending the CrPC to allow for the release of an under-trial prisoner who has been in detention for half of the maximum sentence awardable to him if he was convicted,[91] and liberalising rules around interviews with relatives, friends and lawyers for prisoners.[92] Based on the recommendations of the Supreme Court,[93] a Model Prison Manual was drafted in 2003 as a guide for States to draw from, and adopt best practices.[94]

In 2016, the Ministry of Home Affairs approved a new Model Prison Manual.[95]

While it is largely based on the Prison Manual, 2003 there were a few changes with respect to under-trial prisoners’. The manual has expanded the categories of under-trial prisoners on the basis of ‘security’, ‘discipline’ and ‘institutional programme’.[96] However, the categorisation still does not reflect the difference between a pre-trial and an undertrial prisoner. The biggest change in the Prison Manual is the inclusion of a chapter on legal aid, providing for appointment of jail visiting advocates, legal aid clinics in every prison, and constitution of under-trial review committees.[97] It remains to be seen whether these changes in the Model Prison Manual reflect in the State Manuals, and manifest as visible progress in the prisons as not all States have adopted the Model Prison Manual in its true spirit.[98]

Prison Laws in Karnataka

The Prisons Act, 1894 is the central law for prisons in India.[99] It deals with maintenance of prisoners, appointment of officers of prison and their duties, admission, removal and discharge of prisoners, prisoner discipline and employment of prisoners. However, prisons, reformatories, and borstal institutions are State subjects under the Constitution of India, 1950.[100] Thus, each State has both legislative and executive power over prisons. Prisons in Karnataka are governed by the Karnataka Prisons Act, 1963, the Karnataka Prisoners Act, 1963, the Karnataka Prison Rules, 1974, the Karnataka Prisons Manual, 1978,[101] the Borstal School Act, 1963 and the Borstal School Rules, 1969.

(a) Segregation Of Prisoners

4.53

Section 5 of the Karnataka Prisons Act, 1963 mandates the State Government to construct and regulate prisons so as to facilitate separation of different categories of inmates.[102] Women are to be separately housed from the men, male prisoners under the age of 21 years should be separated from the other prisoners, under-trial criminal prisoners must be separated from convicts, and civil prisoners must be kept apart from criminal prisoners.[103] The Act allows prisoners under trial to see their legal advisers without the presence of any other person.[104] The Model Prison Manual 2003 also mandates the separation of prisons according to categories of prisoners.[105] It defines an ‘undertrial’ prisoner as one who has been committed to custody in prison, pending investigation or trial,[106] thereby clubbing ‘pre-trial’ and ‘under-trial’ prisoners.[107]

(b) Overcrowding In Prisons

4.54

In an attempt to deal with overcrowding, in Re Inhuman Conditions in 1382 Prisons[108] the Supreme Court directed the Inspector General of Prisons to identify the jails where overcrowding is 150% and above and prepare an action plan to reduce overcrowding. The Manual tackles the overcrowding problem by providing for a court hall to be set up in the prison to dispose of cases of under-trials involved in petty offences.[109] Under-trial prisoners must be produced before the court either in person or through electronic media and a court diary must record instances of production, on the basis of which police escort should be requested in advance.[110]

Higher courts in India have also failed to engage with the competing purposes of a bail decision, despite having upheld the cardinal rule of ‘bail not jail’ on more than one occasion.148 As under-trials are legally presumed innocent with little evidence to suggest guilt, any time spent in prison deserves justification. Excessively long prison time, even prior to establishing guilt of the detainee is a matter of individual and societal concern due to its long-term debilitating effects on a person’s health, income and employability, as well as costs to the family and the society at large.149 Research in the US150 and other jurisdictions151 has confirmed these consequences and suggests that detention at this preliminary stage ‘puts many on a cycle of incarceration from which it is extremely difficult to break free’.152

4.55

Further, the Manual provides that under-trials whose cases have been pending for more than three months should be sent on the fifth day of each month to the Sessions Judge or District Magistrate with relevant extracts to the court concerned.[111] Timely presentation of the accused before the magistrate is crucial for the case to progress and avoid unnecessary and prolonged confinement. However, in Karnataka, it was found that between September 2014 and February 2015, a monthly average of 2,490 under-trial accused were not produced in court due to shortage of police escorts.[112] For every 100 police escorts requested, only 70 were sent for production of the accused.[113]

(c) Periodic Review Mechanism

4.56

In Bhim Singh v. Union of India,[114] the Supreme Court directed the establishment of District level Under-Trial Review Committees (UTRCs), in furtherance of the series of decisions by which the it had renewed its attention on the large numbers of under-trial detainees.[115] The Court noted that the Central Government, in consultation with State Governments, must take steps to fast track all types of criminal cases so that criminal justice is delivered in a timely and expeditious manner. The mandate of the UTRC is to exercise oversight over unnecessarily long incarceration of under-trial prisoners, particularly those detained under Section 436A, CrPC, persons who have been granted bail but are unable to furnish sureties and persons detained for compoundable offences.[116] Since their establishment, it has been noted that while UTRCs have been formed in quite a few districts and good practices have been observed in some of them, meetings are irregular and compliance with the intended mandate of the UTRC are patchy.[117]

“The current scenario on bail is a paradox in the criminal justice system, as it was created to facilitate the release of accused person but is now operating to deny them the release.”[118]

Conclusion

4.57

In its 268th Report, while reviewing the definition and purpose of bail in India, the Law Commission noted that “The current scenario on bail is a paradox in the criminal justice system, as it was created to facilitate the release of accused person but is now operating to deny them the release.”[119] However, despite the lament, the Law Commission failed to weigh competing principles or values that guide bail decision making and suggest an analytical framework.

4.58

In performing the balancing act between crime control and due process concerns while making bail decisions, three challenges of ensuring equity, rationality and visibility are evident.[120]

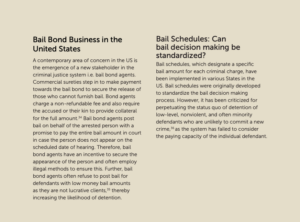

4.59

Equity demands that similarly situated accused persons are treated alike in terms of both process and outcome. This leads us to the principle challenge of identifying the driving factor behind a bail decision. Should a positive bail outcome depend solely on the financial capability of the accused? Alternatively, are factors like seriousness of the charge, community ties and circumstances of the accused more relevant? However, this is a difficult determination in any legal system in the absence of consensus on the main purpose behind a bail decision[121] or a framework by which competing values may be weighed.

4.60

Rationality and visibility are intricately tied to a discussion on equity in bail decision making. Rationality requires a direct link between the criteria for decision making and the intended bail outcome.[122] However, where money bail is the predominant mode of securing bail in a legal system, a determination on bail and corresponding period of detention, as well as the factors driving it are ‘low visibility’ occurrences,[123] as the ability to furnish bail is entirely dependent on the financial strength of the accused person.[124]

4.61

Higher courts in India have also failed to engage with the competing purposes of a bail decision, despite having upheld the cardinal rule of ‘bail not jail’ on more than one occasion.[125] As under-trials are legally presumed innocent with little evidence to suggest guilt, any time spent in prison deserves justification. Excessively long prison time, even prior to establishing guilt of the detainee is a matter of individual and societal concern due to its long-term debilitating effects on a person’s health, income and employability, as well as costs to the family and the society at large.[126] Research in the US[127] and other jurisdictions[128] has confirmed these consequences and suggests that detention at this preliminary stage ‘puts many on a cycle of incarceration from which it is extremely difficult to break free’.[129]

4.62

An argument may be made that the number of under-trial prisoners in India is the result of the failure to consider how each stage of the criminal justice process differs and consequently, how the prioritisation of considerations while making bail decisions should also vary at each stage. The legal framework governing criminal procedure, from arrest to sentencing, suggests that a useful distinction between the pre-trial (which begins with an arrest and concludes with the filing of chargesheet) and under-trial (which begins with the filing of charge-sheet and the ends with the trial decision) stages ought to be made in the criminal justice process. Nonetheless, at every stage, bail decision making should surface the three core values of equity, rationality and visibility.

4.63

So far, in this Chapter, we have analysed the statutory and doctrinal framework on bail decision making in India and identified certain substantive and procedural ‘due process’ considerations, which have also been recognised and reiterated in judgments of the higher judiciary. We will return to this tussle between competing values at the end of this report, but now we turn to analyse the data on bail decision making at first productions and in the pre-trial stage, collected through court observations and from court records.

References

- Section 437(1), CrPC: “When any person accused of, or suspected of, the commission of any non-bailable offence is arrested or detained without warrant by an officer in charge of a police station or appears or is brought before a Court other than the High Court or Court of session, he may be released on bail...” Section 437(2), CrPC: “If it appears to such officer or Court at any stage of the investigation, inquiry or trial, as the case may be, that there are not reasonable grounds for believing that the accused has committed a non-bailable offence, but that there are sufficient grounds for further inquiry into his guilt, the accused shall, subject to the provisions of section 446A and pending such inquiry, be released on bail, or, at the discretion of such officer or Court, on the execution by him of a bond without sureties for his appearance as hereinafter provided.” ↵

- Section 436(1), CrPC: “When any person other than a person accused of a non-bailable offence is arrested or detained without warrant by an officer in charge of a police station, or appears or is brought before a Court, and is prepared at any time while in the custody of such officer or at any stage of the proceeding before such Court to give bail, such person shall be released on bail: Provided that such officer or Court, if he or it thinks fit, may, and shall, if such person is indigent and is unable to furnish surety, instead of taking bail from such person, discharge him on his executing a bond without sureties for his appearance as hereinafter provided.” ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167 read with Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 57. ↵

- In Talab Haji Hussain v. Madhukar Purshottam Mondkar, the Supreme Court briefly touched upon the issue when it noted the contradictory classification of some offences under the IPC. Talab Haji Hussain v. Madhukar Purshottam Mondkarand, 1958 AIR 376, 1958 SCR 1226 (Supreme Court of India). ↵

- Law Commission of India, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, (154th Report, 1996). ↵

- 'Report of the Committee on Reforms of Criminal Justice System’ (Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003) Volume 1, 184 <http://mha.nic.in/sites/upload_files/mha/files/pdf/criminal_justice_ system.pdf> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵

- ibid ↵

- The Report illustrates the absence of a consistency and rationale in the classification by illustrating that subjecting a woman to cruelty (Section 498A, IPC) is punishable with three years imprisonment and is non-bailable, while committing adultery (Section 497, IPC) is punishable with imprisonment up to five years and is bailable. See Law Commission of India, Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, (154th Report, 1996). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 173 ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 436. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 2(c). Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 41 allows the arrest of a person without a warrant. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 156(1). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 2(r). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 155. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 155(3); As per Section 155(4), a case with both cognizable and non-cognizable offences is considered as a cognizable case. ↵

- Sheela Barse v. State of Maharashtra (1983) 2 SCC 96. The Supreme Court issued guidelines on arrest. ↵

- D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal, (1997) 1 SCC 216. The Supreme Court issued guidelines on arrest and detention. ↵

- Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar, AIR 2014 SC 2756. The Supreme Court issued directions to the Centre and noted that “Our endeavour in this judgment is to ensure that police officers do not arrest accused unnecessarily and Magistrate do not authorise detention casually and mechanically.” ↵

- Sheela Barse v. State of Maharashtra (1983) 2 SCC 96. ↵

- ibid. Some of these safeguards have also been codified in Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 50A which requires the person who is arresting another, to convey information of the arrest to a person nominated by the arrestee, to inform the arrestee of this right, and to record the arrest in a book at the police station. ↵

- D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal, (1997) 1 SCC 216. ↵

- D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal, (1997) 1 SCC 216. ↵

- Joginder Kumar v. State of Uttar Pradesh (1994) 4 SCC 260. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2008 (5 of 2009). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 41(1). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2008 (5 of 2009) ↵

- Sections 41B and 50A reiterated the guidelines in D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal, (1997) 1 SCC 216; Sheela Barse v. State of Maharashtra (1983) 2 SCC 96, Joginder Kumar v. State of U.P. (1994) 4 SCC 260). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, s 41A(4). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, s 50(a). ↵

- See Second Schedule, Form no. 3 (Bond and Bail-bond after arrest under a warrant), and Form no. 28 (Bond and Bail-Bond on a preliminary inquiry before the police officer). ↵

- Proviso to Code of Criminal Procedure, s 436(1). ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(1). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 172 mandates the investigating officer to record proceedings related to the case in a diary every day. The details include the time at which the information reached him, the time at which he began and ended his investigation, places visited by him, statement of the circumstances ascertained through investigation, and statements of witnesses recorded during investigation. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(2). ↵

- Raj Narain v. Supdt.Central Jail, 1971 AIR SC 178; Gouri Shankar Jha v. The State of Bihar and Ors., 1972 AIR SC 711. The case dealt with CrPC, 1898, which had the same provisions of production within the first 24 hours. ↵

- Joginder Kumar v. State of Uttar Pradesh, (1994) 4 SCC 260. In this case, the Supreme Court recognised the need for a ‘balance’ between the rights of the accused and the need to protect the society. The Court said that arrests must not be made in a routine manner and without reasonable justification. ↵

- Constitution of India, 1950, Article 22; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(1); Raj Narain v. Superintendent, Central Jail, AIR 1971 SC 178 ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 436(2). ↵

- Section 437(4) CrPC. ↵

- Rao Harnarain Singh Sheoji Singh v. The State, AIR 1958 P&H 123; State v. Captain Jagat Singh, AIR 1962 SC 253; State v. Jaspal Singh Gill, 1984 AIR SC 1503; Raghubir Singh & Others Etc v. State of Bihar,1987 AIR SC 149; Ram Pratap Yadav v. Mitra Sen Yadav, (2003) 1 SCC 15. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437(5). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437(1)(i). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437(1)(ii). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(2)(b) proviso. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(2)(b) proviso. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(2)(b) proviso. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(2)(b) Explanation 1. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437. ↵

- Section 438, which deals with grant of anticipatory bail for nonbailable offences, lists out in sub-section (2), the conditions that may be imposed while granting anticipatory bail such as (i) enjoining the presence of the arrested person for interrogation by a police officer when required, (ii) non-interference in the investigation and (iii) approaching the court for prior permission before leaving India. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437(3). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 440: Amount of bond and reduction; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 441: Bond of accused and sureties; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 441A: Declaration by sureties; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 442.: Discharge from custody; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 443: Power to order sufficient bail when that first taken is insufficient; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 444.: Discharge of sureties; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 445: Deposit instead of recognizance; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 446: Procedure when bond has been forfeited; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 446A: Cancellation of bond and bail bond; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 448: Bond required from minor; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 450: Power to direct levy of amount due on certain recognizances. ↵

- Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967, s 43D(5) proviso. ↵

- Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, s 37. ↵

- Narcotics Control Bureau v. Kishan Lal, (1991) 1 SCC 705. ↵

- Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967, s 43D(4). ↵

- Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, s 18. ↵

- Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967, s 43D(2)(b), UAPA; Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, s 36A(4) ↵

- Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985 s 36A(4) proviso. ↵

- State of Madhya Pradesh v. Kajad, (2001) 7 SCC 673. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437(7); Further, a person may be released on bail if at any stage of the investigation, inquiry or trial, the court feels that there are no reasonable grounds to believe that the accused has committed a non-bailable offence, but that there needs to be further inquiry into his guilt. However, where such accused was released prior to filing of the charge sheet, release on bail alone is not a sufficient ground to bring an accused back into custody. See Basin v. State of Haryana (1977) 4 SCC 410. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437(6). ↵

- Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee Representing Undertrial Prisoners v. Union of India and Anr., (1994) 6 SCC 731, JT 1994 (6) 544; Re - Inhuman Conditions In 1382 Prisons, (2016) 10 SCC 17. ↵

- See generally Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, ch XIX; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 235; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 248. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 437A. ↵

- Andrew Ashworth and Mike Redmayne, Criminal Process (4th edn., 2010) 229. These four grounds for refusal of bail have been recognised by the European Court of Human Rights at Strasbourg. ↵

- ibid at 228. ↵

- Safeguards for protection of an accused person’s due process rights have also been codified in various international instruments such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 (Article 11(1)), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 (Article 9(3)), European Convention on Human Rights, 1950 (Article 6(2)) and standards such as the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-Custodial Measures (Rule 6.1), United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Rule 111). Further, these instruments emphasise that detention should be pursued only as a matter of last resort. Also see Eur. Court HR, Case of Tomasi v. France, judgment of 27 August 1992, Series A, No. 241-A, p. 36, para. 91, cited in Office of High Commission on Human Rights (OHCHR), Human Rights in the Administration of Justice: A Manual on Human Rights for Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers, 194. ↵

- Article 22, Constitution of India, 1950 directs that the person arrested and detained in custody shall be produced before the nearest magistrate within 24 hours of such arrest. Only in two situations can this mandate be obviated: 1. When the person arrested is an ‘enemy alien’, or 2. When the arrest is under any law for preventive detention ↵

- Constitution of India, 1950, Article 22(3). ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 57; Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, s 167(1). A related right against custodial torture has been recognised by the court in Nilabati Behera v. State of Orissa, AIR 1993 SC 1960; Bhim Singh v. State of Jammu & Kashmir, AIR 1986 SC 494; Sheela Barse v. State of Maharashtra, 1983 SCR (2) 337. In all these cases, the courts have found the police/armed forces/ other public officers culpable of severe forms of custodial violence and awarded exemplary compensation to the victim/their families. ↵

- Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India, 1978 SCR (2) 621; Khatri (II) v. State of Bihar and Ors., (1981) 1 SCC 627. ↵

- A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak, AIR 1992 SC 170. ↵

- Supreme Court Legal Aid Committee Representing Undertrial Prisoners v. Union of India and Anr., (1994) 6 SCC 731, JT 1994 (6) 544. ↵

- Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 2005 (25 of 2005). ↵

- Husain and Another v. Union of India, Criminal Appeal No. 509 of 2017. ↵

- Mohd. Ajmal Amir Kasab v. State of Maharashtra, (2012) 9 SCC 1. ↵

- Khatri (II) and Ors. v. State of Bihar and Ors., 1981 SCR (2) 408. Also see Suk Das v. State of Arunachal Pradesh, 1986 SCR (1) 590. ↵

- Mohd. Ajmal Amir Kasab v. State of Maharashtra, (2012) 9 SCC 1. ↵

- Nandini Satpathy v. P. L. Dani, (1978) 2 SCC 424; Hussainara Khatoon (IV) v. State of Bihar, (1980) 1 SCC 98; Mohd. Ajmal Amir Kasab v. State of Maharashtra, (2012) 9 SCC 1. ↵

- Law Commission of India, Amendments to Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 – Provisions Relating to Bail (268th Report, May 2017); ‘Report of the Expert Committee on Legal Aid: Processual Justice to the People’ (Department of Legal Affairs, Government of India, 1973) <http://reports.mca.gov.in/Reports/15-Iyer%20committee%20 report%20of%20the%20expert%20committee%20in%20legal%20 aid,%201973.pdf> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵

- Prem Shankar Shukla v. Delhi Administration, (1980) 3 SCC 526. ↵

- Citizens for Democracy v. State of Assam, (1995) 3 SCC 743; Sunil Gupta v. State of Madhya Pradesh, (1990) 3 SCC 119. ↵

- Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration, (1978) 4 SCC 494; Sunil Batra (II) v. Delhi Administration, (1980) 3 SCC 488. ↵

- Sanjay Suri & Anr. v. Delhi Administration & Anr., 1988 Supp SCC 160. ↵

- See ‘Part I of the National Policy On Prison Reforms and Correctional Administration’ (Bureau of Police Research & Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2007). ↵

- ‘All India Committee on Jail Reform’ (Bureau of Police Research & Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, 2003). ↵

- ibid para 4.34.18. ↵

- ibid para 4.34.19 and 12.17.21. This recommendation was implemented in 2005 when Section 436A was inserted into the Code of Criminal Procedure. ↵

- ibid paras 6.19.1 & 12.17.16 ↵

- Ramamurthy v. State of Karnataka, (1997) SCC (Cri) 386. ↵

- ‘Model Prison Manual for the Superintendence and Management of Prisons in India’ (Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003). ↵

- ‘Union Home Minister approves New Prison Manual 2016’ (Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India) <http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=134687> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵

- The three categories now are: •‘Red’ category: Fundamentalists, Naxalites, extremists, terrorists. •‘Blue’ category: gangsters, hired assassins, dacoits, serial killers/ rapists/violent robbers, drug offenders, habitual grave offenders, communal fanatics, prisoners highly prone to escape or attack other prisoners. •‘Yellow’ category: those who do not pose any threat to the society on release, those involved in murder on personal motives, other bodily offences, property offences, special and local laws, railway offences and minor offences. ↵

- See Model Prison Manual 2016, ch XVI. ↵

- Letter of the Joint Secretary No.17014/3/2009-PR (Ministry of Home Affairs, 17 July, 2009), <https://mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/ PrisonAdvisories-1011.pdf> accessed 22 November 2019. ↵

- The Prisons Act, 1894. ↵

- Constitution of India, 1950, 7th Schedule, list II, item 4. ↵

- The Karnataka Prisons Manual, 1978 is inaccessible and has not been uploaded on the website of the Karnataka Prisons Department or any other Government website. See ‘Conditions of Detention in the Prisons of Karnataka’ (Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, 2010) 1. ↵

- Karnataka Prisons Act, 1963, s 5: Accommodation for prisoners — The State Government shall provide, for the prisoners in the State, accommodation in prisons constructed and regulated in such manner as to comply with the requisitions of this Act in respect of the separation of prisoners. Also see Section 26, Karnataka Prisons Act 1963. ↵

- Sunil Batra (II) v. Delhi Administration, (1980) 3 SCC 488. ↵

- Karnataka Prisons Act, 1963, s 40. ↵

- ‘Model Prison Manual for the Superintendence and Management of Prisons in India’ (Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003), Rule 2.02. ↵

- ‘Model Prison Manual for the Superintendence and Management of Prisons in India’ (Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003), Rule 1.31. It also includes those whose sentence execution has been suspended by the Court, or is under appeal, those whose sentence has been annulled and are ordered by the Court to be retried, and a warrant for the prisoner’s release on bail is not received. (Rule 10.38). ↵

- ‘Model Prison Manual for the Superintendence and Management of Prisons in India’ (Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003), Rule 2.05 (xiv). Mentally sick under-trial prisoners, young under-trial offenders and women under-trials must not be lodged with other under-trial prisoners: Rule 22.01. ↵

- Inhuman Conditions in 1382 Prisons, In Re, (2016) 14 SCC 815 ↵

- ‘Model Prison Manual for the Superintendence and Management of Prisons in India’ (Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003), Rule 2.06.5. We are unable to find how many prisons have set up courts in the prison premises. ↵

- ‘Model Prison Manual for the Superintendence and Management of Prisons in India’ (Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003), Rules 22.21 and 22.22. Also see Code of Criminal Procedure, s 167(2). ↵

- ‘Model Prison Manual for the Superintendence and Management of Prisons in India’ (Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2003), Rule 22.40. ↵

- ‘Justice Under Trial: A Study of Pre-trial Detention in India’ (Amnesty International India, 2017) 10 <https://amnesty.org. in/justice-trial-study-pre-trial-detention-india/> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Bhim Singh v. Union of India, (2015) 13 SCC 603. ↵

- See Chapter 1, Introduction. Also see Hussainara Khatoon and Others v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar, 1979 AIR 1369; Sunil Batra v. Delhi Administration, (1980) AIR 1579; Rama Murthy v. State of Karnataka, (1997) 2 SCC 642; Bhim Singh v. Union of India, 2014 SCC Online SC 682; Re - Inhuman Conditions In 1382 Prisons, (2016) 10 SCC 17. ↵

- ‘Circle of Justice: A National Report on Under Trial Review Committees’ (Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, 2016) < https://www.humanrightsinitiative.org/publication/circle-of-justicea-national-report-on-under-trial-review-committees> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Law Commission of India, Amendments to Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 – Provisions Relating to Bail (268th Report, May 2017). ↵

- ibid. ↵

- John S. Goldkamp and Michael R. Gottfredson, ‘Bail Decision Making and Pretrial Detention: Surfacing Judicial Policy’, (1979) Law and Human Behavior, 3(4) 227. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- In State of Uttar Pradesh v. Amarmani Tripathi, (2005) 8 SCC 21 as cited in Sanjay Chandra v. CBI, (2012) 1 SCC 40, the Supreme Court listed out a host of considerations to be considered while making a bail decision: (i) whether there is reasonable ground to believe that the accused committed the offence, (ii) the nature and gravity of the charge, (iii) severity of the punishment, (iv) danger of absconding, (v) character, behaviour, means and position of the accused, (vi) likelihood of re-offending, (vii) apprehension of witnesses being intimidated and (viii) danger of justice being thwarted by grant of bail. However, there has been little engagement on the primary purpose behind bail in India and further, no guidance was provided on how the multitude of considerations must be weighed against each other. ↵

- Jayanth, K. and Kumar, C. Raj, ‘Delay in Process, Denial of Justice: The Jurisprudence and Empirics of Speedy Trials in Comparative Perspective’ (2011) Vol. 42 Georgetown Journal of International Law. ↵

- ‘Moving Beyond Money: A Primer on Bail Reform’ (Criminal Justice Policy Program, Harvard Law School, 2016); ‘Incarceration’s Front Door: The Misuse of Jails in America’ (Vera Institute of Justice, February 2015) 5 <https://www.vera.org/publications/incarcerationsfront-door-the-misuse-of-jails-in-america> accessed 23 November 2019; ‘The Price of Freedom Bail and Pretrial Detention of Low Income Non-felony Defendants in New York City’ (Human Rights Watch, 2010) <http://www.pretrial.org/wpfb-file/the-price-offreedom-human-rights-watch-2010-pdf/> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵

- Cape, Ed and Smith, T, ‘The Practice of Pre-trial Detention in England and Wales: Research Report’ (University of the West of England, Bristol, 2016) <http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/28291> accessed 23 November 2019; Bamford, David, ‘Factors Affecting Remand in Custody: A Study of Bail Practices in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia’ (Australian Institute of Criminology, Research and Public Policy Series, 1999) 23 <http://www.aic.gov.au/media_library/ publications/rpp/23/rpp023.pdf> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵

- ‘Incarceration’s Front Door: The Misuse of Jails in America’ (Vera Institute of Justice, February 2015) 5 <https://www.vera.org/ publications/incarcerations-front-door-the-misuse-of-jails-inamerica> accessed 23 November 2019. ↵