5.1

As we discussed in Chapter 4, ‘first production’ is the first point of the criminal justice process where there is judicial oversight over the custody of the accused. Here, the court decides whether to grant bail to the person produced before it.

5.2

Briefly, a court must consider four grounds – (i) preventing the accused from absconding during the investigation and trial, (ii) preventing the commission of further crime on release, (iii) preventing tampering with evidence or intimidating witnesses and (iv) preventing public disorder that may result from releasing an accused involved in a serious crime. In this Chapter, we move from law in the books to law in action. In particular, we examine how bail decisions are made in three districts in the State of Karnataka.

5.3

In Chapter 2, we introduced the empirical strategy developed to understand the factors shaping bail decision making in court and its effect on pre-trial and under-trial detention in India. The first strategy was direct court observation of bail decision making in first production cases. A fuller account of the methodology is set out in Chapter 2. In this Chapter, we focus on the results of this approach.

5.4

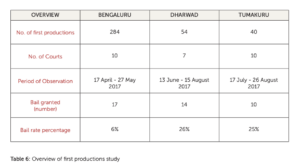

We observed a total of 378 cases of first production, in 6 weeks of court observations in Bengaluru, Dharwad and Tumakuru,[1] comprising;

Bengaluru – 284,

Dharwad – 54,

Tumakuru – 40.

5.5

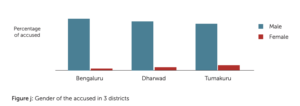

Almost all the accused produced in court during the court observation period were men (Figure j). Tumakuru, with 10%, had the highest percentage of accused women, while only 3% of the accused produced in Bengaluru were women. Apart from the gender of the accused, no other demographic information was available.

5.6

At first production of an accused, three outcomes are possible. First, the accused may be released on bail. Second, the court may remand the accused to police custody for further investigation. Third, the court may direct the accused to judicial custody, resulting in imprisonment. Generally, an accused person prefers bail and where bail is refused, to

be remanded to judicial custody. Police custody is the least preferred outcome as it could expose the accused to physical and psychological assault by the police.

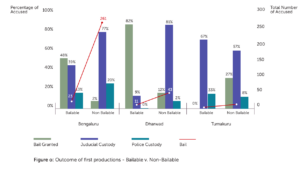

5.7

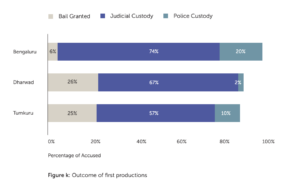

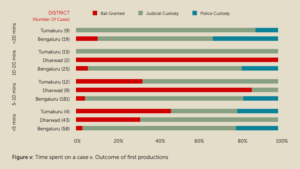

Figure k presents an overview of the outcomes at first production in the cases observed in this study. In all three districts, judicial custody was the outcome of first production in more than 50% of the cases. In Bengaluru, 74% of first productions resulted in judicial custody, with Dharwad and Tumakuru recording 67% and 58%, respectively. Police custody was granted only in 1 in 5 cases in Bengaluru and 1 in 50 cases in Dharwad. Notably, in Bengaluru, the number of police custody orders was three times that of orders granting bail.

5.8

This cursory review of the outcomes of first production in the three districts reveals no clear pattern. While the substantive law discussed in Chapter 4 may give the impression that bail is the default option on first production, in the observed cases, judicial custody is the most likely outcome.

Bail was granted in about 25% of the cases in Dharwad and Tumakuru but in only about 6% of the cases in Bengaluru.

This wide variation in the rate of bail being granted between the three districts may be due to the types of cases in each court or the factors that shape bail decision making. We explore these questions in the rest of this Chapter.

A. Explaining First Production Outcomes

5.9

The preliminary figures on bail outcomes at first production reflect stark differences between the 3 districts.

This suggests that the location or situs of the criminal proceedings, and first production in particular, could determine whether an accused is granted bail or is remanded to

judicial / police custody. However the variations between the 3 districts cannot simply be attributed to geography but is more reasonably explained by differences in policing strategies, court and prosecutorial cultures.

The data collected through the court observations and court records do not provide ready answers on the nature and extent of differences between the three districts on these counts. However, our study allows us to identify and explore some of the substantive and procedural legal factors that may contribute to these differences and are relevant to a bail decision.

5.10

Substantive factors relate to the nature of the offence and its classification. Procedural factors are tied to due process considerations and include effective legal representation and treatment of the accused among others. In the following sections, we will present our findings on how such substantive and procedural factors shape the outcome of a bail decision.

I. SUBSTANTIVE FACTORS

5.11

Our study considered the impact of two substantive factors that could influence a bail decision – (I) statutory basis and nature of the offence, and (II) type of offence i.e. classification of offences as bailable and non-bailable. The IPC and the CrPC, as well as criminal statutes recognise both these factors to be relevant to bail decision making. So, let us examine their effects in turn.

(a) Statutory Basis Of Offence

5.12

Criminal offences can be broadly categorised as offences under the IPC and offences under SLLs. SLLs is a category developed by the NCRB to include a wide variety of non-IPC criminal statutes, which range from laws to protect children to terrorism offences. As a first step, it is useful to review how IPC and SLL offences are dealt with at first production.

5.13

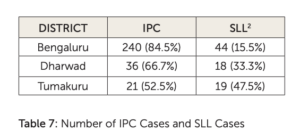

The statutory basis of offences in the three districts is widely variant. If the bail decision outcomes differ across these statutes, then this may explain the wide variation in outcomes across the three districts. In Table 7, we notice that while it is equally likely that an offence before a Tumakuru court is an IPC or SLL offence, it is 5 times more likely to be an IPC offence in Bengaluru.

5.14

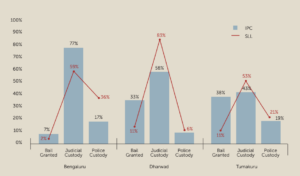

Among both IPC and SLL offences,[3] the most likely outcome of a bail decision was found to be judicial custody. Irrespective of the specific offence, police custody was not granted in the case of any IPC offence in Dharwad and was granted only in 6% of SLL offences. Accused persons were at least three times as likely to secure bail for an IPC offence when compared to an SLL offence. In Bengaluru and Dharwad, accused persons were twice as likely to be remanded to police custody for SLL offences than IPC offences, though in Tumakuru, the chances were similar.

5.15

Between the three districts, most number of SLL offences were registered under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO) and the NDPS Act. The POSCO does not restrict the powers of the court to grant bail and extends the provisions of the CrPC on bail to offences under it. However, as discussed in Chapter 4, the NDPS Act designates particular offences under it as nonbailable and further places fetters on the powers of the court to grant bail. Further, the general view that offences under such special statutes are grave in nature may also explain the reduced bail outcomes in case of SLL offences.

Figure l: Statutory basis of offences and outcomes of first production[4]

5.16

Therefore, two trends stand out from the data collected through court observations. First, the common trend in all three districts was that bail was granted at higher rates for IPC offences when compared to offences committed under an SLL. Second, significant variations in the outcome on first production are visible across the three districts depending on whether the offence committed was under the IPC or an SLL (Figure l).

5.17

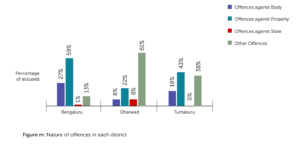

IPC offences can be further categorised into offences against the body, offences against the property, offences against the State and public order, and other offences which may be a combination of any or all of them. While data on types of offences and its relationship with bail outcomes could be collected in the court observations in Bengaluru, such an analysis could not be carried out in respect of Dharwad and Tumakuru as the number of IPC offences were too small[5] to draw any significant conclusions.

5.18

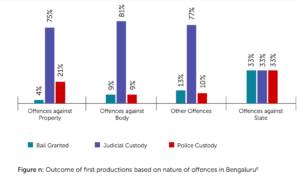

On comparing the nature of offences, we see that in Bengaluru, the lowest rate of bail was in case of offences against property, though we may expect the rate of bail to be the least for offences against the body. Surprisingly, offences against the State have the highest rate of bail being granted (Figure n). Despite concerns that persons accused of such offences may potentially create public disorder, the rate of bail is high, which raises questions on whether such offences may be politically motivated.

5.19

Therefore, there is a significant variation of bail rate across the category of offence and hence this may partially explain the variation across the three districts.

(b) Type of Offences: Classification as Bailable v. Non-Bailable

5.20

As we noted in Chapter 4, offences are categorised into bailable and non-bailable offences under the CrPC. Under Section 436, bail must be granted to persons accused of bailable offences, while under Section 437, courts have discretion to grant bail in case of non-bailable offences.

5.21

Bail may be secured at the police station for bailable offences and only those accused persons who have been refused bail by the police seek bail in court. While this is true of non-bailable offences as well, we see that in practice, police bail is rarely granted and most cases go to court. Consequently, when we undertook this study, we expected only a few bailable cases to reach the criminal courts.

5.22

This expectation was confirmed in Bengaluru (8%) and Tumakuru (8%). However, in Dharwad, 20% of the first production cases were bailable in nature. Non-bailable cases constituted a high proportion of first production cases in all three districts.

5.23

If the classification of offences into bailable and non-bailable in Schedule – I of the CrPC is meant to reflect the seriousness of the offence, then one may presume that bail is more likely to be granted in cases of bailable rather than non-bailable offences at first production. The results from Bengaluru (48%) and Dharwad (82%) aligned with this expectation. However, Tumakuru courts did not grant bail to any accused in a bailable offence at first production.

5.24

In Bengaluru and Dharwad, bail was predictably granted in far fewer non bailable cases, while in Tumakuru, courts granted bail in a significant 27% of non-bailable cases. Across the three districts, judicial custody was the most common outcome in cases of nonbailable offences – 77% in Bengaluru, 81% in Dharwad and 57% in Tumakuru.

5.25

Therefore, we see that the variation in bail rates between the three districts may be explained by the differences in whether the offence committed is under the IPC or an SLL, the type of offence and its classification as bailable and non-bailable.

II. PROCEDURAL FACTORS

5.26

In the analysis of bail decision making in the district courts in this Chapter, we have distinguished between two factors. First, the substantive legal factors that make up the types and categories of criminal offences that are designed to have an effect on bail outcomes. Secondly, we identify the procedural elements of bail decision making that may potentially shape bail outcomes. In this section, we focus on two procedural factors – legal representation and due process in court decision making. We look at each on turn.

(a) Legal Representation

5.27

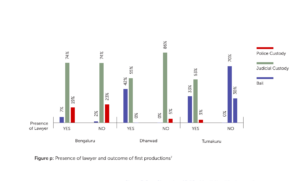

In all three districts, on an average, more than twothird of the accused had legal representation. This was as high as 85% in Bengaluru going down to 75% and 61% in Tumakuru and Dharwad respectively.

5.28

42% of accused persons in Dharwad and 33% of accused persons in Tumakuru having legal representation secured bail. However, it is significant to note that no person who was unrepresented by a lawyer secured bail. Even in Bengaluru, the accused was 3 times as likely to secure bail if they had legal representation, suggesting that the legal representation in fact leads to a positive bail outcome (Figure p).

5.29

The effects of legal representation on judicial custody were less clear. In Bengaluru, legal representation appeared to have no effect as those without legal presentation had an equal chance of being remanded to judicial custody, while more unrepresented accused secured judicial custody orders in Dharwad and Tumakuru.

5.30

Finally, the absence of legal representation appears to have resulted in greater police custody outcomes. In Tumakuru an accused person was 10 times more likely to be remanded to police custody where a lawyer was not present.

While the number of police custody outcomes also increased in Dharwad where there was no legal representation, a clear relationship could not be established as there were too few cases. However, surprisingly in Bengaluru, police custody was granted in a significant 19% of the cases where accused persons were represented by a lawyer.

5.31

Therefore, in all three districts, legal representation had the ability to secure bail orders as the bail rate increased with greater legal representation,

which would have a significant effect on under trial detention. The results with respect to judicial custody and police custody were mixed, suggesting that the inability of legal representation to singularly ensure an order granting bail may be due to the simultaneous influence of factors apart legal representation, such as the nature of the offence.

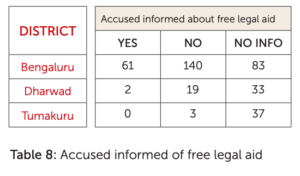

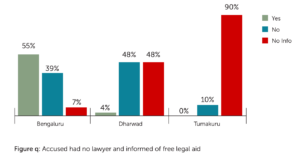

5.32

As observed above, not all accused persons had legal representation at the time of first production. In Chapter 4, we noted that the Supreme Court has made it mandatory for the Magistrate to inform the accused of their right to free legal aid. In this study, we assessed the extent to which this mandate is being complied with.

5.33

We found that in Bengaluru, 55% of the accused (24) who had no legal representation were informed of the right to free legal aid. As expected, in most cases where a lawyer was already present, there was little discussion about legal aid. Therefore, it is salient to look at only those cases where no lawyer was present to assess whether accused persons were informed of their right at first production (Figure q)

5.34

However, as information on this aspect was not available in a substantial number of cases, no clear conclusion on the protocol of informing the accused or its influence on bail outcomes could be drawn.

5.35

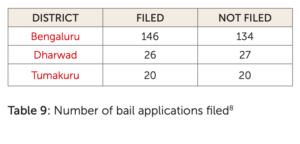

Having noted above that even where a lawyer was present, an accused did not always secure bail at first production, we now turn to examine whether effective legal representation increased the chances of securing bail. Effective legal representation or the quality of legal representation received may be gauged through outcomes or through the procedural steps to secure the outcomes. In this section, we take the filing of a bail application as a symbol of effective legal representation to avoid more subjective assessments of the quality of advocacy.

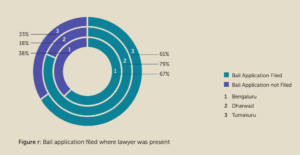

5.36

In all the cases where an accused had no legal representation, no bail application was filed during first production. Bail applications were filed in a majority of cases i.e. 79%, 67% and 61% of cases where the accused had legal representation in Dharwad, Tumakuru and Bengaluru, respectively (Figure r).

5.37

Figures s shows that in Bengaluru, bail was granted in 11% of cases where bail applications were filed and in 78% of the cases, the accused were remanded to judicial custody despite filing of bail applications on first production.

5.38

In all three districts, filing of bail applications appears to have increased the chances of bail being secured. In fact, in Bengaluru, judicial custody was the most likely outcome irrespective of whether a bail application has been filed, while in Dharwad and Tumakuru, judicial custody was almost the default outcome only when no bail application was filed. It must be noted here that the first production outcomes in Figure r above do not distinguish between whether the offence is classified as bailable or non-bailable. However, the classification of offences should make a difference to the relationship between filing of bail applications and bail outcomes.

5.39

As we discussed in Chapter 4, under the CrPC, bail is required to be granted for bailable offences. In Bengaluru alone, out of 18 bailable cases where a bail application was filed, bail was secured in over 50% of cases. However, bail was granted only in 1 out of 5 (20%) bailable cases where no bail application was filed.

Notably, in Dharwad, all persons accused of bailable cases secured bail where an application was filed while surprisingly, in Tumakuru, the none of the 3 persons accused of a bailable offence secured bail, irrespective of whether a bail application was filed.

5.40

In conclusion, we note that effective legal representation can have a significant positive effect on bail being granted and consequently, on under trial detention. However, the persisting variations in outcomes in the three districts, even in bailable offences where bail is to be granted as a matter of right, suggests that there are several other factors that must be investigated.

(b) Due Process Factors

(i) Handcuffing of Accused

5.41

In Chapter 4, we noted that the Supreme Court had ruled that no accused can be produced in court in handcuffs[9] and handcuffing is only intended for persons accused of serious offences or having a prior history of flight risk. In our court observations we noted two distinct practices relating to handcuffing – first, where the accused is produced before the court in handcuffs and second, where the accused was not produced before court in handcuffs, though they may have been in handcuffs before and after production.

5.42

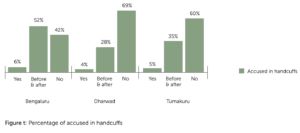

We found that the police follow the norms relating to minimal and reasoned use of handcuffs at the time of first production.

While all three districts had a small percentage of cases where the accused was produced in handcuffs at the time of first production (Figure s), Dharwad and Tumakuru recorded a high rate of compliance with the directions of the Supreme Court as 69% and 60% of the accused respectively, were without handcuffs during the entire period that they were present within court premises.

However, in Bengaluru, 52% of the accused were in handcuffs before and after but not during production before the Judge.

5.43

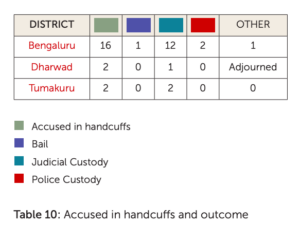

We also probed into whether being produced in handcuffs had any effect on first production outcomes.

5.44

Judicial custody was granted in 15 out of a total 20 cases in which the accused was produced in handcuffs across the three districts. In two cases in Bengaluru, the accused was sent to police custody and in only one case, the court granted bail to the accused (Table 10). While no definitive conclusions may be drawn on this small sample, at first blush, handcuffing appears to indicate lower bail outcomes.

(ii) Role of The Judge

5.45

The fourth and final procedural factor we also set out to analyse was the influence of the decision making process adopted by the judge on outcomes at first production. In order to assess this, we observed two forms of interaction between the accused person and the court – (a) whether the accused was permitted to address the court directly and (b) amount of time spent on a case.

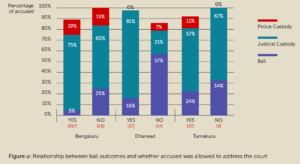

5.46

We found that in 90%, 69% and 93% of cases in Bengaluru, Dharwad and Tumakuru respectively, the accused was allowed to address the court directly. However, surprisingly, bail was more likely to be granted in cases where the accused did not address the court, especially in Dharwad (57%).

5.47

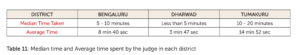

The average time spent on each case was 8.67 mins in Bengaluru and 14.87 mins in Tumakuru (Table 11). We note that there is no standardised judicial approach to bail decision hearings at first production across the three districts, which did not appear to be driven by case load in the courts.

5.48

In Tumakuru, no bail orders were passed where the judge spent more time on a case i.e. over 10 mins, though the chances of bail being granted were notably high where the judge spent less time on a case.

However, in keeping with the expectation that devoting more time to a case would result in more positive bail orders (without accounting for who is addressing the court in this period), bail was a more likely outcome in Bengaluru and Dharwad where the court spent over 10 mins on a case.

5.49

Due process has been conceptualised in two ways in the criminal justice process – instrumental and dignitarian. The instrumental model prioritises accuracy in application of substantive rules to the case leading to correct outcomes, while the dignitarian model focuses on the dignity the accused, their self-respect and autonomy.[10]

5.50

From an instrumental point of view, an accused being allowed to address the court and the time spent by the court on a case had non-linear effects on bail outcomes and wide variations were observed between the three districts. Therefore, in this section, we observed that bail outcomes were shaped lesser by due process factors when compared to substantive law factors. However, from the perspective of a dignitarian model, factors such as not placing the accused in handcuffs during first production, informing the accused about legal aid and permitting the accused to address the court, are being adhered to by courts.

Conclusion

5.51

Thus far, legal reform, and particularly court decisions, has focused on the dignitarian model of due process. While undoubtedly the effects of due process protections on the under trial population are important, the varied results from the three districts direct that greater attention must be paid to substantive law.

5.52 The nature of the offence alleged against an accused made a significant difference to bail outcomes, as IPC offences were more likely to be granted bail than SLL offences. Using the data on statutory basis for offences in Bengaluru, presented earlier in this Chapter, the number of under trial prisoners who would additionally be granted bail may be projected.

In our sample, if the rate of bail in IPC offences is applied to SLL offences, an additional 1% of under trial prisoners would be granted bail for every 100 under trial prisoners, which would make a significant dent in the under trial population.[11] Therefore, we must look deeper into the rationale behind classifying a significant number of SLL offences as non-bailable and the strict conditions imposed in these statutes on bail decision making.

5.53

Along similar lines, bail was a more common outcome in bailable cases when compared to non-bailable cases, suggesting that re-classification of offences under Schedule – I of the CrPC to categorise more offences as bailable is the need of the hour.

5.54

Apart from the type of the offence, presence of ‘legal representation’ was a factor that increased the chances of a positive bail outcome in all three districts, though the three districts reported widely varying effects. In particular, where bail applications were filed, there was an increased likelihood of bail being granted across districts.

However, to standardise practice in this regard, a bail proforma to be prepared and filed at first production may be created, to be used by lawyers and accused persons alike.

5.55

Finally, the widely varying results across the three districts in Karnataka strengthens the suggestion earlier in this Chapter that bail decisions are intricately tied to varied police, court and prosecutorial cultures that collectively reflect as differences based on ‘geographical location’. The reasons for the dissimilarities are not immediately evident from this data set and require further study. However, taking off of these preliminary findings through the Court Observations study, in the next chapter we explore if there is a discernible pattern in these results using data gathered from court records.

References

- We observed first productions, i.e. where the accused persons were first produced in court for a period of 45 days in these districts. To obtain a reasonable number of observations, we chose district courts that had a significant number of cases from Karnataka. See Chapter II of this report for a detailed explanation on methodology ↵

- The most commonly invoked SLLs invoked in the 3 districts are: (i) Bangalore – Narcotic and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985; Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956; Arms Act, 1959. (ii) Dharwad – Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012; Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989; Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881. (iii)Tumakuru – Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012; Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956; Karnataka Police Act, 1963. ↵

- For each district, we have calculated the percentage of outcomes within IPC and SLL cases separately (using the numbers mentioned in Table 5). For example, bail granted among IPC cases is 7% of the 240 IPC cases in Bengaluru. ↵

- The overall figures do not add up to 100% as the outcomes apart from the three principle outcomes – bail, judicial custody and police custody – have been included in the total. ↵

- In Dharwad, of the 36 offences under the IPC, bail was granted in respect of 12 ‘other offences’ while 7 accused were remanded to judicial custody. Further, 14 persons were remanded to judicial custody for offences committed against the body, property and the State. Tumakuru also presented similar numbers with bail being granted to 8 accused for ‘other offences’ while 13 accused were remanded to judicial custody for offences against the body and property. No offences against the State were observed in Tumakuru. ↵

- The overall numbers do not add up to 100% on account of rounding off. ↵

- In Bengaluru, a significant 240 accused persons were represented by a lawyer while 44 persons were unrepresented. Similarly, in Dharwad, 33 persons had legal representation and 21 persons did not. In Tumakuru, lawyers were present in court for 30 accused persons, compared to 10 persons without legal representation. ↵

- In some cases in each district, there is no information provided on whether bail application was filed or not. ↵

- Prem Shankar v. Delhi Administration, AIR 1980 SC 1535(Supreme Court of India) ↵

- Hayley Hooper, Between Power and Process: Legal and Political Control over (Inter)national Security, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 38(1) (2018). ↵

- The percentage of under trial prisoners who would additionally receive bail is subject to the proportion of IPC and SLL offences. ↵