Smriti Parsheera and Vishal Trehan

I. Introduction

The mobile telecommunications sector serves as the backbone for digital information flows in the country. Over 97% of subscribers in India rely on the wireless communication services offered by telecom service providers (“TSPs”) as the primary means of internet access.[1] Competition among TSPs and changes in the structure of this market, therefore, have a critical bearing on how users interact with the information economy.

The mobile telecommunications sector has witnessed several key changes post Reliance Jio’s[2] (“Jio”) disruptive entry in September, 2016. The ensuing developments have taken the market in a very different direction from where it was just five years back, in terms of the number of operators, price structures, number of subscribers and their usage patterns (See Table 1).[3] [4] The sector continues to evolve, most recently with the Adani Group announcing its intention to set up a private 5G network although it would not be competing with the TSPs in the consumer mobility space.[5]

Table 1: Key changes in the Indian telecom sector

|

Parameter |

Mar, 2015 | Mar, 2022 |

| No. of Internet subscribers | 302.3 million | 824.8 million |

| Active operators (TSPs) | 12 | 5 |

| Average data consumption | 91.5MB | 15.8GB |

| Average outgo per GB | Rs. 200 | Rs. 10.4 |

| Monthly average revenue per user

(% from data usage) |

Rs. 122

(17.6% from data) |

Rs. 127

(85% from data) |

Source: TRAI’s quarterly and monthly performance reports[6]

The period following Jio’s entry is often spoken about in the context of telecom ‘price wars’ and ensuing mergers and exits by firms that could not cope with market pressures. But Jio has also played another notable role in shaping the current structure of the market by pushing for greater convergence between telecom and content services and the bundling of handsets with telecom services. Jio’s bundled smart-features phone with 4G-LTE capabilities are designed as affordable phones that are meant to serve the gap between basic mobiles and smartphones.[7] It, therefore, entered the market not only with a price-differentiated strategy but also a technology-differentiated one.[8] In July 2020, Jio received investments of over Rupees 1520 billion from 13 investors, which included digital behemoths Google (7.73% stake) and Facebook (9.99% stake).[9] Existing TSPs responded to these developments with innovations of their own, including revised tariff plans, network improvements, and bundling of services. Subsequently, Bharti Airtel and Google also announced a partnership that would lead to Google holding a 1.28% stake in the telecom company together with other commercial arrangements.[10]

While the telecom industry’s basic structure could be characterised as a ‘natural oligopoly’,[11] we now have a much tighter oligopoly than before. Industrial organisation studies draw a link among increased concentration, higher prices, and higher profits for TSPs.[12] Oligopolistic markets are also known to be more susceptible to both active and tacit forms of collusion.[13] Further, the existence of vertically integrated structures in such markets creates possibilities of foreclosure of competition and mandatory bundling of goods and services. However, there remains a divergence in views about whether concentrated markets necessarily lead to anti-competitive effects, or if they could foster greater efficiency.[14]

Drawing the link between market structure and effects becomes particularly difficult in heavily regulated sectors like telecommunications, where outcomes are shaped by a mix of market developments and regulatory factors. Regulatory decisions on the pricing of telecom services, terms of spectrum auctions, and permissible relationships between telecom and content providers are some examples of such factors. Regulatory interventions often create entry and exit barriers, which are an important feature of market structure. Concentration levels, product differentiation, and extent of vertical integration are some of the other relevant structural elements. An understanding of these features lays the foundational block for analysing the state of competition and potential effects of any anti-competitive conduct in the telecommunication sector.

The Competition Commission of India (“CCI”) also took note of these issues by commissioning a report on competition issues in the telecom sector. The report makes pertinent observations on topics such as the importance of non-price factors like quality of services and data speed, vertical integration in the sector, unbundling of the infrastructure and service layers, data privacy concerns, and inter-regulatory interactions.[15]

In this paper we take a closer look at the structural developments in this sector post Jio’s arrival in the market. We do this based on a survey of the relevant literature on competition in the digital communications sector, a review of the CCI’s decisions, and analysis of the monthly subscriber data and quarterly performance indicator reports released by the Telecommunication Regulatory Authority of India (“TRAI”). A significant portion of the discussions revolve around examining the role of market structure in understanding the competitive outcomes in the mobile telecommunications sector, with a focus on market concentration and vertical relationships. This forms the starting point for understanding the behaviour of firms and consumers in the telecom market. Our analysis points to two key trends – growing concentration in the mobile telecom market and increasing cross-links across the telecom, content and device layers. Although these developments are not unique to India, their effects on the conduct and performance of markets are indeed shaped by the local context.

In a span of four to five years Reliance Jio managed to acquire over 30% of the telecom market share in 15 of the 22 telecom circles.[16] Its share in the internet services segment is even higher, where it represents 53.17% of the country’s internet subscriber base across mobile and wired connections.[17] The company has also started rolling out its fibre-to-the-home connections although, so far, it is reported to have seen lesser success on this front compared to its wireless services.[18] Jio, however, scored a big win over its competitors through its investments haul in 2020.

While Jio’s entry and business strategies and the competitive responses of other firms are an important part of the story, there are certain other dimensions of Jio’s market power, which might not always be captured in a formal competition analysis.[19] In this context, we highlight the criticality of recognising the political economy forces that are at play in this sector. Focusing in particular on Facebook’s investment in Jio we argue that Jio’s dominance must be viewed not just in light of available knowledge about concentration and market power in the telecom sector but also the reality that flows from it being a part of the Reliance conglomerate. Its place in the Reliance conglomerate, its recent strategic alliances, and a carefully curated image of being a swadesi counter to global big tech are all determinants of Jio’s soft power. We argue that it is this interaction between market power and soft power that will ultimately shape the sector’s competitive outcomes. Given the link between telecom markets and internet access and the trend of convergence between the network and content layers, concentration of power in this space also bears significant implications for information generation, access and control on the internet.

Against this background, the rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section II outlines the relevance and key determinants of market structure in the telecom sector. Section III then offers an empirical analysis of the developments in market concentration levels in different circles of India’s telecom market during the period between 2015-22. This period corresponds with the entry of Jio into the market and consequent changes in the structure and behaviour of the market. Section IV follows with a discussion on the trends and implications of vertical relationships in the sector, particularly across the access, content, and device layers. Next, in Section V, we explore some of the other determinants of the ‘Jio effect’, including its recent partnerships with the likes of Facebook and Google. We conclude in Section VI with a discussion of the broader implications of the structural and soft power effects of Jio for the future of competition and digital governance.

II. Understanding Market Structure

Market structure refers to the characteristics of a market, taking into account the nature of the relationships between buyers and sellers, and among different sellers in that market.[20] It is shaped by a mix of intrinsic structural elements that relate to the nature of the product and technologies involved and derived elements, such as concentration levels, regulatory policies, product differentiation, and historical factors.[21] Collectively, these factors determine whether a market reflects the characteristics of a monopoly, oligopoly, or perfect competition. In the case of telecommunication services, intrinsic structural elements would include differing features of mobile and fixed-line services, and variations in successive generations of wireless technologies (i.e., 2G, 3G and 4G LTE). On the other hand, factors such as licensing requirements, spectrum costs, scale efficiencies, and product bundling are examples of key derived elements. In this section, we explain the relevance of market structure in market performance and competition studies and explore the possible ‘relevant markets’ that can be demarcated in the telecom sector.

A. Relevance of Market Structure

Economic theory suggests that certain types of market structures enable, or at least increase the likelihood of, certain types of conduct. In particular, the nature and scope of collusive conduct in a market is often related to the prevalent structural and legal conditions.[22] Further, structural changes affect the price discrimination strategies of firms and thus have important welfare consequences. Studying these links for the wireless communications industry is particularly important since technological innovations and entries/exits lead to interesting effects on the market structure.[23] The structure-conduct-performance (“SCP”) paradigm, which has been a popular framework of analysis in industrial organisation studies,[24] posits a causal connection between an industry’s market structure, the conduct of firms, and the performance of the industry and firms.[25] This leads to an assumption that the level of concentration in an industry determines the pricing, investments and marketing decisions of firms, which in turn affects their performance. However, in practice, the reverse may also be true – the conduct or performance of firms can shape the market structure. For instance, mergers and investments can result in a change in concentration levels and marketing strategies can impact product differentiation.[26] Therefore, the link between structure, conduct, and performance is not always unidirectional in nature.

Challenges such as these have led to a questioning of the relevance of the SCP framework in competition practice.[27] However, it still remains a commonly deployed frame of analysis in telecommunication research studies. To take an example, a 2014 study of market concentration across OECD telecom markets applied the SCP analysis to establish a link between concentration, higher prices and profits.[28] Other international studies have also evinced the relationship between structure and performance in this sector.[29] Looking beyond the academic applications of the SCP framework, regulatory practices also signal the broader relevance of market structure analysis. Notably, in the telecom sector, authorities often perceive the existence of certain structural characteristics, like the prevalence of oligopolies, as an indicator of higher risk of anti-competitive effects.[30]

In recent years, scholars like Lina Khan have also made a case for the revival of economic structuralism as the standard for understanding competition issues in digital markets.[31] [32] This literature focuses mainly on structural issues in the markets for online services and platforms, shaped both by the lack of sufficient regulatory oversight in this space and the inadequacy of traditional metrics like ‘price’ and ‘output’ to analyze the conduct of online platforms.[33] While examining the dominance of online platforms like Amazon, Lina Khan argues that the ‘consumer welfare’ standard that became prevalent with the rise of the Chicago school ought to be discarded in favour of understanding the ‘underlying structure and dynamics of the market’.[34] She notes that economic structuralism offers the opportunity to focus on the competitive process through which firms gain anti-competitive power.[35] In a more recent article, Lina Khan reviews the historical application of structural prohibitions in the US.[36] She argues, albeit again in the context of digital platforms, that structural separation – a traditional regulatory principle for addressing the challenges posed by dominant firms – be given its “seat back at the table.”[37]

While the jury is still out on whether structuralism can completely replace the consumer welfare standard in the context of the United States, current practices in India show that competition and regulatory agencies already place a fair degree of reliance on structural aspects. The Competition Act, 2002 requires market structure analysis to be the starting point for evaluating competitive effects in many circumstances. For instance, it lists factors like market share, size of the firm and its competitors, and extent of vertical integration as being relevant to any assessment of market dominance.[38] The CCI also takes market structure into account while reviewing merger and acquisition transactions. Recently, while assessing the merger between Vodafone India Limited and Idea Cellular Limited, CCI noted that despite the effect of increasing concentration in certain telecom circles, the transaction was not likely to have any appreciable adverse effect on competition. This was done taking into account the likelihood that competitors would be able to exercise adequate competitive constraints on the merged entity, switching ability of buyers, and the likely efficiencies from the combination.[39]

Further, both TRAI and the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) also tend to rely on market structure analysis in many contexts, such as the regulation of predatory pricing, setting interconnection charges, and recommendations on mergers and acquisitions.[40] For example, TRAI’s recommendations to the Government in 1999 on the introduction of competition in National Long Distance (NLD) communications included a detailed analysis of the structure of the NLD market and an evaluation of different arrangements for increasing competition. DoT’s 2014 merger guidelines prescribed market share limits for evaluating merger and acquisition proposals, and other proposed arrangements between companies. The guidelines set a hard limit of fifty percent of the market share for any entity resulting from a merger or acquisition.[41] More recently, in 2018, TRAI adopted a tariff regulation specifying a threshold of thirty percent as an indicator of significant market power.[42] This approach of setting hard limits on market shares differs from the case by case determination followed by the CCI.

B. Elements of a Market Structure Analysis

We now move from discussing the relevance of market structure to elaborating the components of such an analysis. This typically consists of four key elements.

- Market Share and Level of Concentration

In general, a higher market share indicates a greater possibility of market power. CCI’s practice shows that it may consider various metrics, such as overall quantum of spectrum, total number of subscribers, net subscriber additions, and gross revenue, as the basis for calculating market shares.[43]

Unlike market shares, which offer a firm-specific indicator, concentration ratios reflect the concentration of market share in the hands of a small number of firms. For instance, an N-firm concentration shows the degree of concentration among the top ‘N’ number of firms. Herfindahl Hirschman Index (“HHI”) is another commonly used indicator. Calculated as the sum of the square of the market share of each of the firms, HHI reveals the relative size distribution of the firms in a market.[44] Although, as we discuss later, there exist some concerns about its suitability for the telecom sector, HHI still remains a popularly used tool of analysis. For instance, the CCI has used it in a number of cases while analysing the effect of proposed combinations on the market.[45]

The computation of HHI can be combined with the use of the Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient to show the unevenness in the distribution of market shares. The Lorenz curve is a graphical representation of market share among all the players, where a 45 degree line represents a perfectly equal distribution.[46] The Gini coefficient is a related measure used for studying inequality of shares – a Gini value of 0 represents complete equality in distribution of market share, while a value of 1 indicates a monopoly.[47]

- Barriers to Entry and Exit

The barriers to entry and exit in the market could be in the form of legal, economic or strategic barriers. Mandatory licensing requirements, restrictions on use of spectrum, and other compliance requirements are types of legal barriers. Economic barriers would include the large fixed and sunk costs involved in operating a telecom business and strategic barriers are ones that arise due to the behaviour of other firms in the market. For example, the refusal of incumbent players to provide sufficient points of interconnection to a new entrant would constitute a strategic barrier.[48]

- Product Differentiation

The degree of product differentiation in the market is shaped by factors like technology, tariff, quality, availability, and customer groups.[49] While there seems to be a basic degree of standardisation in the product offerings of wireless service providers – data, voice and SMS services that are usually offered as a bundle – there is still scope for differentiation based on pricing and quality of services. Further, the bundling of video subscription services with mobile tariff plans, which we discuss later, is another type of product differentiation strategy.

- Vertical Integration

The fourth relevant factor is the extent of vertical integration or vertical separation, namely decisions regarding “how many stages of the production process take place within the firm.”[50] Over the years, industrial organisation literature has offered contrasting views of the competition effects of vertical integration. While the SCP perspective of the 1950s and 1960s raised concerns about exclusionary practices, the Chicago School later contended that vertical integration increases efficiency.[51]

In the subsequent sections we analyse the developments in India’s telecommunications market along two of these dimensions – concentration and distribution of market shares (Section III) and vertical relationships (Section IV). This choice is motivated by market share and concentration analysis generally being seen as the starting points for understanding the power dynamics in any market and our focus on the ‘Jio effect’, with vertical integration being one of its defining characteristics.

C. Delineating the Relevant Market

Any analysis of market structure must begin with the identification of the market in question. In competition studies, the concepts of demand and supply side substitution are generally used to demarcate this ‘relevant market’. Demand or consumer side substitution implies the ability of consumers to switch from one product to the other based on factors like price, characteristics and end use.[52] Supply substitution, on the other hand, assesses whether other firms can start producing the product in the short term without significant additional costs.[53] In addition to the product or service-related aspects, the relevant market may also have a geographic dimension. The Competition Act, 2002 defines this to mean an area with homogeneous competition conditions which can be distinguished from other areas.[54]

Defining the relevant market in the telecom sector is not a straightforward exercise. First, the industry encompasses several different types of services – retail and wholesale, wired and wireless, narrowband and broadband, to name a few. Second, the presence of high fixed costs and regulatory barriers limits short-term supply-side substitution.[55] Third, there is a possibility of one-way substitution. For instance, fixed calling can be substituted by mobile calling but not the other way round.[56] Fourth, telecom services are typically consumed in bundles. This can make it harder to evaluate the market for standalone components of the market.[57]

Some of these issues have also come up before Indian authorities but the practice, so far, has been to stick to the regulatory product boundaries while defining the market. In a complaint filed by Airtel against Jio’s free pricing offer, the CCI held that the “provision of wireless telecommunication services to end users” was the relevant market. While doing so it rejected Airtel’s suggestion of designating 4G services as a separate market on the grounds of (i) constant evolution of technology in the sector; (ii) backward compatibility of mobile handsets – a 4G phone would also support 3G services; and (iii) the fact that the telecom licensing conditions do not differentiate between providers based on the technology being deployed. The Commission also noted that the wireless services market did not need to be broken further into data-only services and voice plus data services.[58] The TRAI’s definition of relevant market also looks at wireless access service as a whole as one market without making any distinctions based on the functionality offered by different technologies or differences between voice and data services.[59]

In both the cases, the regulators seem to have opted for a regulatory/licensing design driven approach toward defining the market rather than a consumer substitutability driven one. A more granular segmentation of the market would be preferable given the lack of full substitutability between 2G and 4G services – 4G can support more bandwidth intensive applications than 2G and hence has differing characteristics and end use.[60]

In the case of the geographic market, both CCI and TRAI have held that this needs to be demarcated at the level of the licensed service areas specified for licensing purposes, spectrum allocations and tariff plans. India is divided into 22 such circles. While this is certainly better than looking at a pan-India market, in reality the homogeneous condition from the user’s perspective might be limited to a much narrower area. A telecom circle’s boundary typically extends to one or more states whereas a user’s experience may be limited to specific locations like their residence, workplace or frequently travelled routes. This sort of a granular demarcation, although difficult to implement, becomes even more relevant in case of wired internet access services which see significant variations in the number of providers serving each locality.

For the purposes of market structure analysis in this paper, we primarily focus on competitive conditions in the mobile telecom service market, since it constitutes about 98% of the telecom services market sector in terms of user base. It is also the market that has been most noticeably affected by entries and exits in the last few years. We treat this as the relevant product market and look at the various licensed service areas, or circles, as the relevant geographic markets.

III. Concentration in the Indian Telecom Sector

Jio’s entry into the mobile telecom market in September, 2016 triggered a spate of acquisitions and consolidations. Some of the notable developments include the merger between Vodafone and Idea and Bharti Airtel’s acquisition of firms like Tata Teleservices and Telenor. At the same time, others like Aircel and Reliance Communications ended up exiting the market.[61] As a result of these developments, the market now stands at three private sector players plus the state-owned Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (“BSNL”) and Mahanagar Sanchar Nigam Limited (“MTNL”). Recently, the Indian government has also become the largest stakeholder in Vodafone-Idea pursuant to the decision to convert the spectrum and adjusted gross revenue dues owed by the TSP into equity.[62]

In a 2019 study, Kathuria, Kedia & Sekhani looked at the change in HHI levels across different service areas to study how the telecom market’s structure changed from 2004 to 2018. They noted a trend of increased consolidation in the industry, attributable to the entry of Jio and the subsequent exit of inefficient players.[63] In this section, we undertake a more focused analysis of the concentration trends seen over the last 7 years. We also add to the previous literature by studying the distribution of market shares using Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient. Further, wherever possible, we rely on data about the active users rather than the total number of subscribers.

To begin with, Table 2 shows the market shares for all existing TSPs in each circle as of March 31, 2022. Market shares, and by extension concentration indices, can be calculated using several metrics, including volume-based (call minutes, number of users, data usage), value-based (revenues), or capacity-based (number of lines installed) metrics.[64] For the purposes of the present analysis, we use the number of active subscribers, as reported in TRAI’s monthly telecom subscription reports, as the basis for evaluation.[65] In a few cases where the total subscribers are recorded but the visitor location register (“VLR”) value, which reflects the number of active users, is not available, we use the total subscribers as a substitute.[66]

Table 2: Circle-wise market share (%) in March, 2022

| Circle TSP | Airtel | BSNL | Vodafone Idea | Jio | MTNL | Reliance Comm. |

| All-India | 34.84 | 5.86 | 22.14 | 37.10 | 0.06 | 0.0002 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 41.05 | 7.18 | 16.44 | 35.33 | ||

| Assam | 46.58 | 6.42 | 10.81 | 36.19 | ||

| Bihar | 45.19 | 3.46 | 10.37 | 40.99 | ||

| Delhi | 36.68 | 26.16 | 36.45 | 0.70 | 0.0005 | |

| Gujarat | 19.81 | 4.44 | 36.08 | 39.68 | 0.0001 | |

| Haryana | 28.82 | 8.03 | 30.89 | 32.26 | 0.0001 | |

| Himachal Pradesh | 41.48 | 13.02 | 7.26 | 38.24 | 0.0004 | |

| J & K | 51.76 | 6.47 | 3.44 | 38.33 | ||

| Karnataka | 50.32 | 5.96 | 11.81 | 31.91 | 0.0010 | |

| Kerala | 20.39 | 20.01 | 37.20 | 22.41 | 0.0004 | |

| Kolkata | 25.41 | 4.91 | 25.49 | 44.19 | ||

| Madhya Pradesh | 22.09 | 4.15 | 24.71 | 49.05 | ||

| Maharashtra | 24.69 | 4.87 | 28.76 | 41.69 | ||

| Mumbai | 31.28 | 31.04 | 36.36 | 1.32 | 0.0032 | |

| North East | 50.55 | 7.29 | 8.78 | 33.38 | ||

| Orissa | 37.79 | 11.96 | 5.89 | 44.36 | 0.0001 | |

| Punjab | 39.67 | 7.29 | 22.62 | 30.42 | 0.0002 | |

| Rajasthan | 38.02 | 5.23 | 18.04 | 38.70 | 0.0002 | |

| Tamil Nadu | 36.71 | 9.51 | 23.54 | 30.23 | 0.0004 | |

| Uttar Pradesh (E) | 41.22 | 4.18 | 19.60 | 35.00 | ||

| Uttar Pradesh (W) | 32.62 | 4.28 | 29.21 | 33.89 | 0.0000 | |

| West Bengal | 29.48 | 3.66 | 26.77 | 40.09 | 0.0002 |

It is clear from the table that market shares are not distributed equally across the circles. While there are several circles, such as Delhi, Punjab and Tamil Nadu, where the distribution of market shares is similar to the all-India figures, many other areas reflect a different pattern. Examples of such outliers include Kerala, where Jio has only 22% market share compared to its pan-India share of 37.1% and Gujarat where Vodafone-Idea has a share of 36%, 14% more than its all-India market share.

Considering the small number of players in the market we have excluded the commonly used four-firm and three-firm concentration ratios from our analysis. We opt instead for a HHI analysis along with computation of Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient to analyse the nature of concentration in the market. These measures have been used together in several studies to ‘capture a more complex array of competitive possibilities’ while gauging the concentration levels.[67] [68] Table 3 provides a guide on how to interpret the relationship between these two measures.

Table 3: Relationship between HHI and Gini coefficient[69]

| High Inequality (High Gini) | Low Inequality (Low Gini) | |

| High Concentration

(High HHI) |

Monopolistic | Oligopolistic |

| Low Concentration

(Low HHI) |

Dominated | Atomistic |

A. Methodology

We adopt the following methodology to examine the present status and recent trends of concentration in the mobile services market.

- Time Period

We have done a time-series analysis of HHI values for the seven-year period from March 2015 to 2022, on a quarterly basis. While this shows us the long-term trends, we have also analysed more recent data from March 2022, using both HHI and Gini coefficients, to present a more complete picture of the current state of the industry. While conducting the latter analysis, we have excluded Reliance Communications (“R.Com.”), which has only a minor share of subscribers, from the list of firms.[70] Counting R.Com., which is no longer an active player, would affect the Gini coefficient calculations hence presenting a false picture about the distribution of market shares.

- Relevant Geographic Market

As noted previously, we look at the various licensed service areas, or circles, as the relevant geographic markets. For the March, 2022 analysis, we have looked at concentration measures for each circle whereas the long term HHI trends analysis has been done only for some selected circles. The time-series analysis focuses on a few select circles – Delhi, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh (East) (“UP(E)”), Bihar, and Himachal Pradesh (“HP”). While the first four are the circles with the most number of wireless subscribers in each category of telecom circles (Metros, A, B, C, as defined by the DoT), HP has been chosen owing to its unique status as a state with one of the highest wireless subscriber tele-densities (number of subscribers per 100 population) despite its mountainous terrain and remote areas.

B. Results and Analysis

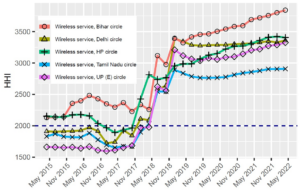

Consistent with the reduction in the number of operators over the last few years, Figure 1 shows that the HHI level in each of the five selected circles has gone up during the study period. In particular, the period from November 2017 to 2018 saw a sharp increase in concentration levels across all circles resulting from the various exits and mergers. Thereafter, HHI values have remained nearly constant or increased/decreased slightly in some circles (Tamil Nadu, Delhi and UP (E)), while they have steadily increased in others (Bihar and HP).

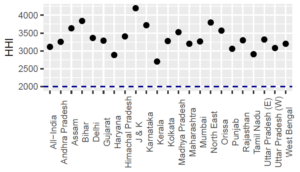

The present HHI levels in the five selected circles are in the range of 2750 to 3800. This is in line with the trend across all the other circles except Jammu & Kashmir, which has a higher HHI level of about 4000 (Figure 2). While these values are higher than the benchmarks that are usually adopted by competition authorities, they are not significantly different from the trends seen in other telecommunication markets.

The US Department of Justice’s merger guidelines classify markets into three categories depending on the HHI – (i) unconcentrated markets: HHI below 1500; (ii) moderately concentrated markets: HHI between 1500 and 2500; and (iii) highly concentrated markets: HHI above 2500.[71] However, a study of market concentration in OECD mobile telecom markets found that the mean value for subscriber-based HHI, calculated using data from 24 countries, was consistently above 3000, during the 1998-2011 period.[72]

Therefore, despite its widespread usage in competition analyses, the suitability of HHI as a measure has faced criticisms, including for its failure to account for industry-specific nuances.[73] For instance, an ex post analysis of certain mergers and acquisitions in the Korean telecom industry observed that although the HHI had increased, it did not necessarily imply an adverse effect on competition. The author argues that, on the contrary, it could be a reflection of the total output shifting towards more efficient larger firms, which can create welfare gains.[74] Similarly, in the Indian context, it has been suggested that increased consolidation might be a sign of the sector’s movement towards a more efficient and mature market with fewer players who are able to focus better on infrastructure expansion and quality of services.[75] TRAI too has noted in the past[76] that HHI may not be a suitable measure for assessing market shares in the telecom sector because it does not take into account sector specific concerns, such as the fact that subdivision of spectrum can hamper efficiency in the market. This means that an increase in the number of operators can, in fact, have an adverse impact on efficient utilisation of spectrum.

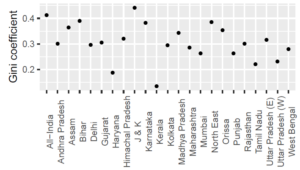

However, rather than abandoning the use of HHI, the criticisms listed above could serve as lessons for its context-specific application. In particular, the use of HHI in conjunction with Gini coefficients can be a useful indicator of the nature of competition in the market. Many circles in India have a high HHI and moderately high Gini value, which as per Table 3 would fall somewhere between a monopoly and an oligopoly.

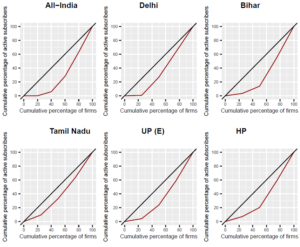

The Gini coefficients shown in Figure 3 indicate that circles such as Bihar, North East, and Karnataka have a more unequal distribution of market shares. Jammu & Kashmir has the highest Gini coefficient value, while Kerala has the lowest. Here, we must point out that the Gini coefficient for circles such as Delhi would be even lower if MTNL, which is a market player in Delhi but has less than 1% share, were excluded from the calculation. If not for MTNL, the Lorenz curve for Delhi in Figure 4 would be significantly closer to the 45-degree line, showing a highly equal market share distribution. The all-India value is also significantly affected by the inclusion of MTNL. As it stands, the Lorenz curve for all-India shows significant divergence from the 45-degree line, with 40% of the firms (i.e. BSNL and MTNL, out of the five firms in the sector) accounting for less than 10% of the active subscribers. Among the circles shown in Figure 4, Tamil Nadu’s Lorenz curve diverges the least from the 45-degree line, meaning that it has the most equal distribution of market share.

Consistent with previous studies on market concentration in India, our HHI analysis reveals that concentration levels have increased across telecom circles in the last seven years. We also add to the previous literature in two ways – first, by focusing on the number of active subscribers instead of total subscribers; and, second, by studying the distribution of market shares using Lorenz curves and Gini coefficient. The Gini coefficient analysis shows that the Indian market as a whole and several circles have a fairly unequal distribution of market shares.

However, in general, the findings for India are not significantly different from the concentration patterns that are generally seen in telecom markets. A part of this may be explained by the very nature of the industry, which tends to be oligopolistic in nature. But high concentration by itself is not an indicator of anti-competitive outcomes and it needs to be studied in combination with other structural and conduct related factors. Accordingly, we focus next on understanding the evolving nature of vertical arrangements in the Indian telecom sector.

IV. Vertical Relationships in the Telecom Sector

Vertical relationships between firms operating at different levels of the production or distribution chain can come about in two main ways. First, it could be a vertical integration of the sort where one entity acquires ownership or control of another business operating in a different layer or offering a complementary product. The merger of AT&T, a major telecom operator, with Time Warner, a content media company, is an example. The US Department of Justice opposed the transaction on the grounds of input foreclosure – the post-merger entity could increase the cost of rivals by increasing prices for Time Warner’s content.[77] Second, such relationships could also come about in the form of commercial arrangements without necessarily having an element of shareholding or control – for instance, where a TSP enters into an agreement with an infrastructure provider to lease its telecom towers,[78] or the bundling of content services and mobile devices with a TSP’s mobile services.

In addition, there could also be a hybrid model that combines the features of vertical mergers and acquisitions and market transactions of the sort described above. These ‘quasi-integration’ arrangements tend to involve the use of debt or equity investments and other means to create alliances between vertically related firms without full ownership.[79] Common forms of quasi-integration include minority equity investment, loans and loan guarantees, exclusive dealing agreements, specialised logistical facilities and cooperative research and development.[80] Such strategic alliances are often seen as a way of lowering capital costs while still retaining corporate identities and avoiding the risk of antitrust prosecution.[81]

In general, competition authorities tend to adopt a more lenient approach towards vertical arrangements, which unlike their horizontal counterparts do not necessarily lead to a reduction in competition. Vertical arrangements that generally involve complementary products could lead to possible efficiency gains and their actual effects remain dependent on the post-transaction conduct of the parties.[82][83] Yet, it is acknowledged that vertical arrangements could bear some harmful consequences, particularly in terms of the foreclosure of competition, through any of the following four strategies: First, and the most common, is input foreclosure – where a vertically integrated firm refuses to supply an input to a downstream competitor or do so on very unfavourable terms; the second type is by impacting the access of competitors to customers; third, by bundling or tying upstream and downstream products, which puts rival products in a disadvantageous position; and lastly, market foreclosure can also occur when a vertically integrated player gains access to commercially sensitive information about its competitors.[84][85]

In this section, we explore the trends in ownership and control of different elements of the telecom value chain. In the context of simplification of licensing norms, the National Digital Communication Policy, 2018 identifies the following layers of the telecom sector – infrastructure, network, services and applications. Our focus here is limited to the downstream relationship between telecom services and the application/content layer.[86] We also discuss the integration of telecommunication services with mobile devices, a practice that has come to the fore with Jio’s line of ‘smart feature’ phones.

A. Integration of Telecom and Content Services

Over the last five years, the bundling of telecommunications services with content has emerged as a popular business strategy among TSPs. This includes the direct ownership of music, video and other content related apps by telecom companies as well as tie-ups with content providers to bundle their offerings with the TSP’s subscription plans. Besides opportunities for direct monetization of content services, TSPs might see content offerings as a path toward product differentiation, customer retention, generating demand for data services, and gathering insights about users. On the other hand, over the top (“OTT”) players might collaborate with TSPs for service distribution, reduced marketing costs, direct carrier billing, and possibility of price subsidisation.[87]

Table 4: Examples of OTT offerings by TSPs

| Service | Airtel | Reliance Jio | Vodafone Idea |

| Music | Wynk Music, Wynk

Tube |

Jio Saavn | – |

| TV & Video | Xstream | Jio TV, Jio Cinema | Vi Movies & TV |

| Ecommerce | Airtel Online store | Reliance Digital (includes JioMart) | – |

| Education | Lattu Kids | Embibe | – |

| Wallet | Airtel Money | Jio Money | – |

| Conferencing | Airtel-BlueJeans | Jio Meet | – |

| Books/ Mags | Juggernaut | Jio Mags | – |

| Others | – | Jio News, Jio Pages,

Jio Health Hub |

– |

Table 4 illustrates how each of the private TSPs has ventured into the OTT space although Jio has a visibly deeper footprint, followed by Airtel. As TSPs expand to these complementary markets, they are not only competing with one another but also with specialised OTT services.[88] During the launch of Jio’s services in 2016, its founder Mukesh Ambani noted that the fundamental pillars of the Jio ecosystem include a broadband network with simplified tariffs, affordable devices, and a bouquet of applications and content.[89] Beside the direct ownership of the telecom and content businesses by Jio Platforms Limited, the company is also able to leverage its relationships with other Reliance group entities. The Reliance Group’s ownership of entertainment and news content and the relationship between Jio and Reliance Retail, an affiliated entity that owns the Reliance Digital, Jio Mart, Ajio and Jio Stores brands, is a case in point. This is discussed further in the next section.

While Jio’s affiliates own a large part of the content on its OTT platforms, other operators have opted for a mix of ownership and collaborations with other content providers. For instance, Airtel’s video streaming app, Xstream, allows users to watch live TV and videos through collaborations with multiple partner apps, including ZEE5, Hungama and Eros Now.[90] Another common trend is for TSPs to offer bundled tariff plans that include subscriptions to paid content. For instance, Vodafone Idea’s RedX plan offers a one-year subscription to Netflix, Amazon Prime and Zee5 for premium post-paid subscribers.[91] The availability of similar plans across different TSPs suggests that such arrangements are being entered into on a non-exclusive basis.

The concerns surrounding the integration of telecom and content services are centered around the gatekeeping capacity of TSPs, the barriers that this may create for competition and innovation, and the accompanying ability to shape the narrative through control over information flows. For instance, a TSP could prioritize the speed and quality of its own content (or that of commercial partners) or create roadblocks for competing content and services. These issues are at the core of the network neutrality debate and India’s adoption of robust principles on this front have laid to rest many of the concerns.[92] These rules bar TSPs from any sort of arrangements that could result in discriminatory pricing of data services or treatment of content.[93] Prevailing content arrangements, therefore, have to be designed to avoid any direct circumvention of these rules. While this helps in reducing the concerns around integration, it does not eliminate them. For instance, content arrangements involving a dominant TSP could negatively impact consumer choice or affect the ability of content providers to gain access to consumers without entering into a tie-up with that TSP.

B. Bundling of Mobile Devices

The bundling of mobile devices with telecom services, specifically in the context of medium range and budget devices, is another key element of Jio’s business model.[94] In 2017, Reliance launched the first generation of Jio Phones, which are 4G enabled feature phones operating on KaiOS. The terms of the offer require the user to pay a refundable security deposit to use a SIM-locked phone for a period of 3 years.[95] Since then, Reliance has launched a second generation Jio Phone and unveiled what it claims to be an `ultra-affordable 4G smartphone’ developed in partnership with Google.[96]

Airtel and Vodafone Idea have also launched bundled phone offerings in partnership with phone manufacturers and financing companies. For example, Airtel has partnered with a range of phone manufacturers where the use of its 4G services for a specified duration entitles the customers to a cash back offer.[97] Similarly, Vodafone Idea had tied up with Home Credit India, to offer financing for the purchase of 4G smartphones in the below Rs. 10,000 category that would be bundled with its prepaid plans.[98] But unlike the Jio Phone, which is manufactured and distributed by entities within the Reliance group, the bundled handsets offerings of other providers have come about through commercial arrangements. As a result, they do not have the same flexibility of cross-subsidisation of phones, data plans and even OTT offerings as Reliance Jio.

In a case relating to a tying arrangement for the sale of Apple’s iPhones by Vodafone and Airtel, the CCI noted that a mobile handset is a complementary product to mobile network service – unless a handset user has access to a mobile network, she would not be able to exploit the full utility of the handset.[99] It then looked at factors such as the market shares of the parties, Apple’s arrangements with other resellers, and effect of consumer choice, and held that the arrangement did not pose any anti-competitive concerns. The CCI’s logic seems sound in light of the fact that neither Apple nor Airtel and Vodafone were found to be dominant players at the time of the analysis. This coupled with the non-exclusive nature of the arrangement meant that consumer choice was not being significantly restricted in the circumstances of the case. However, a similar analysis in the context of Jio’s line of phones could possibly yield different results given the significant market share held by Jio in many circles and the exclusive tying of the Jio Phone with its own mobile network.

V. Other Dimensions of the Jio Effect

The discussions so far have focused on Jio’s entry and business strategies, the competitive responses of other firms, and ensuing changes in the market structure. All of these are important elements of the ‘Jio effect’. However, there are certain other dimensions of Jio’s market power, which might not always be captured in a formal competition/ economic analysis. Teachout and Khan have argued that market structure is inherently political in nature and that concentration and dominance allow companies to exert power in several ‘nonmarket ways’. They categorize these powers into three broad heads – the power to set policy (through campaign funding, recruiting from the government, research funding, etc), the power to regulate (by steering the market and through self-regulation) and the power to tax (by transferring wealth from consumers and suppliers).[100] Building on a similar logic, in this section we focus on the example of Facebook’s investment in Jio to suggest that Jio’s dominance must be viewed not just in light of available knowledge about concentration and market power in the telecom sector but also the reality that flows from it being a part of the Reliance conglomerate, its political character, and perceived role as India’s national digital champion.

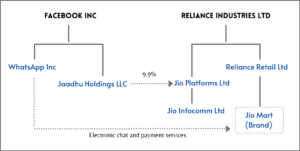

In October, 2020, Facebook acquired a 9.9% stake in Jio Platforms Ltd, which owns Jio’s telecom and digital content businesses. This was accompanied by a master services arrangement between Jio Platforms, Reliance Retail Ltd. and Facebook’s subsidiary, WhatsApp. The agreement provides for the use of WhatsApp’s messaging and payment services for the delivery of Jio Mart services.[101] Jio Mart is a grocery delivery business that connects users with local kirana stores. Its competitors would include the likes of Amazon and Flipkart as well as hyper-local delivery businesses like Blinkit and Dunzo.

The arrangement described in Figure 5 appears to be in the nature of a ‘quasi-integration’, which was discussed in Section IV. Although Facebook has not acquired a controlling stake in Jio,[102] the partnership is designed to achieve certain strategic goals, which include a one-way exclusivity commitment between WhatsApp and Jio Mart.[103] Moreover, even though the investment was made by a large online content player into a telecom business, the crux of the disclosed transaction revolves around two different markets – online grocery delivery and online payments. This illustrates how Jio’s status as a member of the Reliance conglomerate offers it a financing and strategic advantage on account of possible synergies with other complementary businesses.

The relationship between Jio and Reliance Retail also merits scrutiny on another count. In the submissions before the CCI, Jio Mart was described as a business “which is owned by RRL and operated by Jio Platforms”.[104] This highlights a complex internal arrangement according to which Jio Platforms seems to be operating Reliance’s online retail business without being subject to the regulatory requirements that would be attracted from its ownership of the business – such as, restrictions on foreign direct investment. Further, it has been reported that a large portion of Jio Mart’s orders are being fulfilled by Reliance Retail and not local kirana stores.[105] This also raises questions about compliance with foreign direct investment norms, which prohibit foreign investment in inventory-based e-commerce models.[106]

In its analysis of the Facebook-Jio transaction the CCI looked at the horizontal impact of the transaction in competing lines of business – consumer communication services and advertising services – as well as the vertical/complementary relationships. The latter analysis included an examination of the effects of the collaboration on e-commerce and digital payments services and potential data sharing between the parties. The CCI concluded that the proposed combination was not likely to have any appreciable adverse effect on competition in any of the identified markets.

While looking at the possibility of data sharing between the entities CCI noted that “the parties may have incentives to engage in mutually beneficial data sharing”. But it then went on to rely on Facebook’s submissions that data sharing was not the main purpose of the arrangement and that any such processing would be done “in accordance with applicable law and parties’ data policies”. This clarification needs to be seen in light of the fact that until the enactment of the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, there is very little in terms of an applicable law to safeguard the use of personal data.[107] Further, the data policies of the parties can be unilaterally modified at any point of time with no regulatory oversight and a mere notification to users. In fact, Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp offers an example of a similar situation where regulatory approvals were taken on the basis that there would be no exchange of data but the parties went on to revisit this position within a few years. When these changes in the terms were subsequently challenged before the CCI, the Commission found WhatsApp to be dominant in the market for consumer communication apps but declared that there was no abuse of dominance. While doing so, the CCI relied too readily on the clarifications given by the parties about the protection of consumers’ data.[108] WhatApp’s recent updates to its privacy policy, however, prompted the CCI to initiate a suo moto investigation into possible abuse of dominance by the company.[109]

Given the history of the Facebook-WhatsApp transaction, and the extent of Facebook’s, WhatsApp’s and Jio’s market power, the arrangement described above would have been a fit case for the CCI to mandate certain behavioural commitments regarding the parties’ data practices. While the CCI has not laid down any formal guidelines on use of commitments as a merger remedy, it has suggested structural and behavioural commitments in several combination cases.[110] In the present case the CCI could have addressed the concerns of data backed market power by requiring the parties to translate the clarifications given by them into binding commitments. Further, such commitments should have remained in effect at least until such time that an effective data protection regime is put in place.

The debate on Jio’s market power and its potential effects also needs to be located in the broader context of the political economy of India’s digital communications sector. A research study on the political determinants of competition in the telecom industry analysed data from 148 countries to show that government regulation tends to favour telecom operators who are politically connected, thus impacting competitive outcomes. Furthermore, the research also suggests, in the context of Germany, Denmark, and the US, that the level of antitrust activism affects industry consolidation and consequently consumer prices and operator revenues.[111]

Amidst a growing tendency towards technological sovereignty, in India and globally, Jio has managed to position itself as India’s national digital champion. This is supported by its posturing on access and affordability, frequent invocation of the Digital India mission, and support for data localisation initiatives. Arguably, this might have contributed to the decision made by Facebook, Google and many others, to invest in the company. While investors undoubtedly have the discretion to base their strategic decisions on any relevant factors, including realpolitik considerations,[112] this highlights the role of Jio’s perceived power and influence in conferring a competitive and financial advantage on the business.[113] In the concluding section we point to some ways in which the governance of the sector could be better equipped to handle these concerns.

VI. Conclusion

This paper examines the role of market structure in understanding the competitive outcomes in the mobile telecommunications sector. We focus, in particular, on two aspects of market structure analysis – concentration levels and vertical relationships – to examine the ways in which the structure of the market has evolved on both these counts. Our market structure analysis using HHI reveals that concentration levels have increased across India’s telecom circles and the Gini coefficient analysis shows that some circles have a more unequal distribution of market shares. However, the figures are not significantly different from the patterns that are generally seen in telecom markets. A part of this may be explained by the very nature of the industry, which is characterised by high investment costs, dependence on spectrum and regulatory entry barriers.

Telecom markets, therefore, have a tendency to be oligopolistic in nature and a high concentration by itself cannot be seen as an indicator of anti-competitive outcomes. However, this cannot be a ground for complacency. This paper makes a case for a more granular exploration of market structure, which forms a starting point for understanding the behaviour of firms and consumers in the telecom market. Suggested future directions of work would include looking at concentration levels using metrics other than active subscribers and expanding the scope of analysis to also look at the multi-way interaction between the market’s structure and the conduct and performance of its players. This includes an examination of how the increased concentration levels in the Indian telecom markets interact with changes in pricing, investment, quality of services, and revenues.

Jio being part of the Reliance conglomerate, which has immense economic power across multiple sectors, has a direct bearing on the competitive outcomes in the telecom sector. This has played a role in the structuring of Jio’s integrated digital platform, with strong links between the telecom, content, and retail arms of the business. While other mobile service providers are also trying to move in similar directions, their convergence strategies tend to be based on third-party commercial arrangements. This implies a lower chance for cross-subsidisation compared to Jio. Further, Jio’s foray into the digital space is often seen as a swadesi counter to the dominance of foreign firms in the technology arena. This lends broad political support to the business, creating an element of soft power, which might play a role in shaping Jio’s strategic alliances.

Collectively, these factors can have long-term consequences on the state of competition across multiple sectors. Facebook’s recent investment in Jio Platform, where the Reliance group could raise finances for its telecom vertical based on commercial promises made by its retail vertical, is a clear example. While the commercial rationale for such arrangements might remain outside the scope of any formal regulatory analysis, there are some ways in which these concerns could be incorporated into any future inquiry into Jio’s dominance. Besides drawing from the available knowledge about concentration and market power, such inquiries should better account for the size, resources and intra-group commercial arrangements within the Reliance group. Further, any association with technology giants like Google and Facebook, who themselves are under scrutiny, globally, for their anti-competitive and extractive data practices, should be examined more carefully to ensure that the concerns are not being further aggravated.

Dealing with a converged telecom market puts regulatory authorities under the additional burden of not missing the wood for the trees. In other words, analysis of such issues cannot be limited to sector-specific theories of harm but rather must be able to see the inter-links with other complementary sectors. Such harms could, for instance, arise due to foreclosure of competition by parties leveraging their existing customer base, aggregating data across platforms or bundling complementary goods and services. Detecting such harms requires proactive efforts, technical skills, and organisational capacities. In addition to the market surveys that the CCI has started undertaking, seeking pre-emptive commitments and having mechanisms to monitor the post-alliance conduct of firms to ascertain the long-term economic effects, would be in order.

When it comes to the role of the telecom sector regulator, the issue is further complicated due to its limited regulatory mandate, which limits its ability (although not willingness) to look at competition issues across inter-related sectors. It is thus imperative that the CCI, the TRAI, and any other regulatory authority with a complementary mandate, coordinate better and remain vigilant to detect sources of harm to competition and consumers. However, so far, the authorities have shown minimal interest in collaborating on these fronts or building joint capacity initiatives. A joint exercise to understand the multi-way interaction between market structure, conduct and performance, as suggested above, could be the starting point for such a collaboration.

- TRAI, The Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicators July – September, 2021 <https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/QPIR_10012022_0.pdf>, p. ii. ↵

- Reliance Jio Infocomm Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of Reliance Platforms Limited, which in turn is a subsidiary of Reliance Industries (66.48 percent stake). ↵

- Rajat Kathuria, Mansi Kedia, and Richa Sekhani, ‘A study of the financial health of the telecom sector (Working paper no. 380)’ (ICRIER 2019) <https://icrier.org/pdf/Working Paper 380.pdf> ↵

- Competition Commission of India, Market study on the telecom sector in India: Key findings and observations (2021) <https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/whats_newdocument/Market-Study-on-the-Telecom-Sector-In-India.pdf> ↵

- ENS Economic Bureau (2022, July 11). Adani in spectrum race, but ‘not in consumer mobility space’. The Indian Express. <https://indianexpress.com/article/business/companies/adani-in-spectrum-race-but-not-in-consumer-mobility-space-8019984/> ↵

- TRAI, Performance Indicators Reports <https://www.trai.gov.in/release-publication/reports/performance-indicators-reports> and Telecom Subscription Reports <https://www.trai.gov.in/release-publication/reports/telecom-subscriptions-reports>. ↵

- Jeffrey James, ‘The smart feature phone revolution in developing countries: Bringing the internet to the bottom of the pyramid’ (2020) 36(04) The Information Society 226. ↵

- V Sridhar, ‘Reliance Jio’s latest bundling strategy might succeed in improving 4G penetration in India’ (Financial Express) <https://www.financialexpress.com/opinion/reliance-jios-latest-bundling-strategy-mightsucceed-in-improving-4g-penetration-in-india/1090937/> ↵

- Reliance Jio, Media release dated 30 July 2020 <https://jep-asset.akamaized.net/jio/press-release/media_release_jio_30072020.pdf>. The other investors are Silver Lake, Vista Equity Partners, General Atlantic, KKR, Mubadala, ADIA, TPG, L Catterton, Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia, Intel Capital and Qualcomm Ventures. ↵

- Bharti Airtel, Press release dated 28 January 2022 <https://www.airtel.in/press-release/01-2022/airtel-and-google-partner-to-help-grow-indias-digital-ecosystem>. ↵

- Tommaso Valletti, ‘Is mobile telephony a natural oligopoly’, (2003) 22 Review of Industrial Organisation. ↵

- Wolster Lemstra, Nicolai van Gorp, and Bart Voogt, ‘Explaining telecommunications performance across the EU’, [2012]. ↵

- Ashwini Kumar Mishra and Ganesh Rao, ‘Analysing Anti-competitive Behaviour: The Case for Indian Telecom Industry’, 20(1) Science Technology & Society, 21–43. ↵

- Nakil Sung, ‘Market concentration and competition in OECD mobile telecommunications markets’, (2014) 46(25) Applied Economics. ↵

- ‘Market study on the telecom sector in India: Key findings and observations’ (n 3). The report was conducted by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. ↵

- See Table 2 in Section 3 of the paper. ↵

- Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, The Indian telecom services performance indicators (April – June, 2020) <https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/Report_09112020_0.pdf> ↵

- Shubham Verma, ‘RIL AGM 2020: Is Jio Fiber due for upgrade a year later?’ India Today (15 July 2020) <https://www.indiatoday.in/technology/features/story/ril-agm-2020-is-jio-fiber-due-for-upgrade-a-year-later-1700787-2020-07-15> ↵

- See Zephyr Teachout and Lina Khan, ‘Market Structure and Political Law: A Taxonomy of Power’ (2014) 9 Duke Journal of Constitutional Law and Public Policy 37. ↵

- Joe S. Bain, ‘Monopoly and Competition’, Encyclopedia Britannica, (4 Sep. 2019), <https://www.britannica.com/topic/monopoly-economics/Perfect-competition> ↵

- Richard Schmalensee, ‘Inter-industry studies of structure and performance’ in R Schmalensee and RD Willig (eds), Handbook of Industrial Organization (Elsevier Science Publishers BV 1989). ↵

- F.M. Scherer, ‘Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, (Houghton Mifflin, 1990). ↵

- Katja Seim and V. Brian Viard, ‘The effect of market structure on cellular technology adoption and pricing.’, [2011] 3(2) American Economic Journal: Microeconomics. ↵

- Industrial organization refers to the branch of economics that is ‘concerned with the workings of markets and industries, in particular the way firms compete with each other’ per Luis MB Cabral, Introduction to industrial organization (MIT Press 2002) p.3. ↵

- Lemstra, Gorp, and Voogt (n 11). ↵

- Schmalensee (n 21). ↵

- Douglas H Ginsburg and Joshua D Wright, ‘Philadelphia National Bank: Bad economics, bad law, good riddance’ (2015) 80(4) Antitrust Law Journal. ↵

- Sung (n 14). ↵

- Novi Eka Wulansari, Risris Rismayani, and Yudi Pramudiana, ‘Study on structure and performance of telecommunication services industry in Indonesia’ [2015] IEEE, <https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7347229>. ↵

- OECD Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, Competition Committee, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, ‘Vertical mergers in the technology, media and telecom Sector, Background Note by the Secretariat’ (2019). ↵

- Lina Khan, ‘Amazon’s antitrust paradox’, (2017) 126(3) The Yale Law Journal 564. The author however clarifies that she is not ‘advocating a strict return to the structure-conduct- performance paradigm’ (p. 745). This push for the revival of economic structuralism needs to be seen in the context of the legal position in the United States, which accepts the maximisation of consumer welfare as the main goal of antitrust law. See Christine S. Wilson, ‘Welfare Standards Underlying Antitrust Enforcement: What You Measure is What You Get’, Keynote Address at George Mason Law Review 22nd Annual Antitrust Symposium: Antitrust at the Crossroads?, (February 15, 2019), <https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1455663/welfare_standard_speech_-_cmr-wilson.pdf>. ↵

- Lina Khan and Sandeep Vaheesan, ‘Market Power and inequality: The antitrust counterrevolution and its discontents’, (2016) 11(1) Harvard Law & Policy Review 235. ↵

- Khan (n 31). ↵

- Khan (n 31). ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Lina Khan, ‘The separation of platforms and commerce’, (2019) 119(4) Columbia Law Review. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- Competition Act 2002, Section 19(4). The CCI has also relied on a structural analysis while assessing the effects of bundling arrangements in the telecom sector. In Sonam Sharma v Apple Inc USA and others (Case number 24 of 2011), the CCI considered market shares of Apple, Vodafone and Bharti Airtel in the relevant markets to conclude that vertical agreements between them would not have an appreciable adverse effects on competition. ↵

- See Notice under Section 6 (2) of the Competition Act, 2002 jointly given by Vodafone India Limited, Vodafone Mobile Services Limited and Idea Cellular Limited, Jul 31 2017, <https://www.cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/Notice_order_document/Order_C-2017-04-502.pdf>. ↵

- See Telecommunication Interconnection (Reference Interconnect Offer) Regulation 2002. TRAI’s assessment of predatory pricing and interconnection usage charges utilise the concept of ‘significant market power’ which is derived from understanding the market structure and shares of a provider. ↵

- Guidelines for mergers and acquisitions 2014. The resultant entity is required to reduce its market share to 50 percent within one year from the date of approval of the transaction. Similar caps also exist for spectrum holdings at 35 percent of total assigned spectrum and 50 percent spectrum in a specific band. ↵

- Regulation 2(lf) Telecommunication Tariff Order 1999, however, in Bharti Airtel and others v. TRAI (Telecommunication Appeal Nos. 1 and 2 of 2018), the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) struck down this 63rd amendment to the Tariff Order citing the lack of transparency in the guidelines on market shares and pricing. ↵

- See Notice under Section 6 (2) of the Competition Act, 2002 given by Vodafone India Limited, Vodafone Mobile Services Limited and Idea Cellular Limited (n 28). ↵

- HHI can range from 0 to 10,000 where a figure closer to 0 indicates a market occupied by a large number of relatively equal sized firms while a figure closer to 10,000 points to disproportionate control by fewer firms. ↵

- Notice under Section 6 (2) of the Competition Act, 2002 given by Bharti Airtel Limited Combination Registration No. C-2017/10/531, Another parameter that CCI often takes into account is the diversion ratio between the two entities to ascertain whether the removal of the merged entity will lead to an appreciable adverse effect on competition. ↵

- The greater the deviation from this line, the more unequal is the distribution of market shares. ↵

- Bojan Krstić, Vladimir Radivojević and Tanja Stanišić, ‘Measuring market concentration in mobile telecommunications market in Serbia’, [2016] Facta Universitatis, Series 13 Economics and Organization. 247 <casopisi.junis.ni.ac.rs/index.php/FUEconOrg/article/download/1916/1372>. ↵

- ‘Communications panel okays 3,050-cr penalty imposed on Airtel, Voda-Idea’, The Hindu BusinessLine (24 July 2019). <https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/info-tech/digital-commission-approves-3050-cr-penalty-on-airtel-vodafone-idea/article28699917.ece>. ↵

- Katarina Valaskova and others, ‘Oligopolistic competition among providers in the telecommunication industry: the case of Slovakia’ (2019) 9(3) Administrative Sciences. ↵

- Cabral (n 24) p. 3. ↵

- Michael H Riordan, ‘Competitive effects of vertical integration’ [2005] <https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8PN9HVM/download>. ↵

- Section 2(t), Competition Act, 2002. A popular method to assess substitution is based on the small but significant non transitory increase in price test which examines whether a 5-10 percent increase in price would lead users to switch to another product. ↵

- The definition of relevant market in the Indian law presently provides for only the assessment of demand substitution but supply substitution constitutes an integral component of the legal analysis in other jurisdictions like the European Union and the United States. ↵

- Section 2(s), Competition Act, 2002. ↵

- See TRAI, Recommendations of the TRAI on intra circle mergers and acquisition guidelines (2004). ↵

- Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications, Impact of fixed-mobile substitution (FMS) in market definition (BoR (12) 52, 2012) <https://berec.europa.eu/eng/document register/subject matter/berec/reports/363-berec-report-impact-of-fixed-mobile-substitution-fms-in-market-definition>. ↵

- Jordi Gual, Market Definition in the Telecoms Industry, <https://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/telecommunications/archive/telecom/market definition.pdf>. ↵

- However, in an earlier case the CCI had drawn a distinction between GSM and CDMA, which are distinct technologies for commercial mobile services. See Sonam Sharma v. Apple Inc USA and others (n. 26). The reasoning offered was that the same handset could not be used for the two technologies and the supply-side equipment required to deliver the services also differed. ↵

- The other ‘Distinct Telecommunication Services’ identified by TRAI include wireline service, national and international long distance services and any other service for which a licence is granted. ↵

- In Wanadoo Interactive (COMP/38.233), the European Commission demarcated the market for high-speed internet access for residential customers as the relevant market in light of the asymmetrical substitution between low-speed and high-speed internet access services. ↵

- Peter Curwen, ‘Reliance Jio forces the Indian mobile market to restructure’ [2018] Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance. <https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/DPRG-07-2017-0043/full/pdf>. ↵

- Rounak Jain (January 2022), ‘The government is now the biggest shareholder in Vodafone Idea’ Business Insider. <https://www.businessinsider.in/business/telecom/news/vodafone-idea-news-the-government-is-now-the-biggest-shareholder-in-vodafone-idea/articleshow/88824061.cms>. ↵

- Kathuria, Kedia and Sekhani (n 2). Also see, Mishra and Rao (n 8) for an in depth analysis of the market share and concentration trends in the Indian telecom market in the period between 2003-12. ↵

- Subhashish Gupta, ‘Cellular mobile in India: Competition and policy’ [2012] Pacific Affairs 85(3) 483 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/23266770.pdf>. For instance, when defining significant market power as 30 percent of the market share, TRAI adopted the metrics of subscriber base and gross revenue. ↵

- This offers a more accurate parameter than ‘total subscribers’, which may include a number of dormant subscribers. Further, relying on the active subscribers ensures that only the currently active operators are taken to account in the analysis. This explains why Table 2 lists only 6 operators as opposed to the 8 operators reported by TRAI based on total number of subscribers. ↵

- This scenario primarily arose for Jio in September 2016 and for Aircel in March 2018. Thus, the HHI values in these two months may have a small error. ↵

- Bruce A Seaman, Amanda L Wilsker, and Dennis R Young, ‘Measuring concentration and competition in the US nonprofit sector: Implications for research and public policy’ [2014] Nonprofit Policy Forum 5(2) 231 <https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/npf/5/2/article-p231.xml>. ↵

- Valaskova and others (n 46) use HHI and Gini to gauge the level of concentration in Slovakia’s telecom industry. ↵

- Seaman, Wilsker, and Young (n 65). ↵

- R.Com. no longer actively provides telecom services. As per TRAI’s data from March, 2022, it had an Internet subscriber base of just about 1000 users. ↵

- Horizontal Merger Guidelines 2010. ↵

- Sung (n 13). ↵

- Toby Roberts, ‘When bigger is better: A critique of the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index’s use to evaluate mergers in network industries’ [2014] Pace L Rev 34 894. ↵

- Dong-Ju Kim and Sang Taek Kim, ‘Evaluating the effects of horizontal mergers in the Korean mobile telecommunications market’ [2010] International Telecommunications Policy Review 17(3). ↵

- Smriti Parsheera, ‘Building blocks of Jio’s predatory pricing analysis’ [2017] The Leap Blog. <https://blog.theleapjournal.org/2017/04/building-blocks-of-jios-predatory.html>. ↵

- TRAI, Recommendations on Intra Circle Mergers & Acquisition Guidelines (2004). <https://trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/recom%20final-%2030thjan%2020041052012.pdf>. ↵

- United States v AT&T Inc Case 1:17-cv-02511 (DDC, 2017), even though the merger was subsequently allowed by a court, the Department of Justice order disallowing the merger forms an important study of harms arising out of vertical integration. ↵

- A separate class of entities, called Infrastructure Service Providers (Category I) (IP-I) providers, have been authorised to provide passive infrastructure facilities, like telecom towers, dark fibre, right of way assistance and duct spaces, to multiple TSPs. This has led to a hiving off of their tower operations by TSPs and leasing of tower space, either from affiliated or standalone tower companies. ↵

- Michael E Porter, ‘Competitive strategy’ [1997] Measuring Business Excellence. ↵

- Changqi Wu, Strategic aspects of oligopolistic vertical integration, (Elsevier 2017) ↵

- John Stuckey and David White, ‘When and when not to vertically integrate’ [1993] MIT Sloan Management Review 34(3) 71. ↵

- Ferenc Vissi and Patricia Austin, ‘Strategic alliances and global monopolies’ [1997] Russian & East European Finance and Trade 33(2) 73 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/27749387.pdf>. ↵

- D Bruce Hoffman, ‘Vertical merger enforcement at the FTC’, Credit Suisse 2018 Washington Perspectives Conference, (10 January 2018, Washington, DC). <https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public statements/1304213/hoffman vertical merger speech final.pdf>. ↵

- OECD (n 29). ↵

- Guidelines on the assessment of non-horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentration between undertakings 2008, (2008/C 265/07). ↵

- There are also interesting debates on the upstream relationships between the service, network and infrastructure layers. This includes the unbundling of the infrastructure layer through the introduction of IP-I providers and the unbundling of the network and service layers through the virtual network operator (VNO) licensing regime. ↵

- Ovum, OTT media services consumer survey and OTT-CSP partnership study (2019) <https://www.amdocs.com/sites/default/files/Ovum-OTT-market-study-2019-20.pdf>. ↵

- For instance, Airtel and Jio have virtual meeting apps that compete with the likes of Zoom and Microsoft Teams and music streaming apps that compete with services like Gaana and Spotify. In Notice under Section 6 (2) of the Competition Act, 2002 given by Vodafone India Limited, Vodafone Mobile Services Limited and Idea Cellular Limited (n 27) CCI considered mobile wallet services of Vodafone (mPesa) and Idea (Idea Money) as relevant products to gauge whether removal of Idea Money post merger would lead to appreciable adverse effect on competition. This is illustrative of the integration of telecom services with important OTT products. ↵

- In addition to the apps listed above, Jio’s app ecosystem includes an online health management service (Jio Health Hub), a web browser (JioPages) and a news aggregation service (JioNews). ↵

- See, Airtel Xstream: Live TV, Cricket, Movies, TV Shows (apk). In other examples, Airtel’s e-books app came about through an investment in Juggernaut book and its video conference service has been launched in collaboration with Verizon. ↵

- See, Terms and Conditions, Vi, <https://www.myvi.in/content/dam/vodafoneideadigital/documents/PostpaidTnC.pdf>. ↵

- See, Tim Wu, ‘Network Neutrality: Competition, Innovation, and Nondiscriminatory Access’ (2006) <https://ssrn.com/abstract=903118>. ↵

- Smriti Parsheera, ‘Net neutrality in India: From rules to enforcement’ in Luca Belli, Nikhil Pahwa, and Osama Manzar (eds), The Value of Internet Openness in Times of Crisis (UN IGF Coalitions on Net Neutrality and Community Connectivity 2020). ↵

- Bundling of phones in India was previously limited to high-end devices like iPhones or the CDMA phones offered by the now defunct Reliance Communications. ↵

- The use of the phone is bundled with Jio’s telecommunication network and requires the user to spend a specified minimum amount on Jio’s services. ↵

- Manish Singh (June 24 2021), ‘Google and India’s Jio Platforms announce budget Android smartphone JioPhone Next’, Tech Crunch. <https://techcrunch.com/2021/06/24/google-and-jio-platforms-announce-worlds-cheapest-smartphone-jiophone-next/>. ↵

- <https://www.airtel.in/4gphone> ↵

- <https://www.vodafoneidea.com/content/dam/vodafone-microsite/docs/pdf/pressrelease/Press%20Release%-%20VIL%20offers%20Home%20Credit.pdf> ↵

- Sonam Sharma v. Apple Inc USA and others (n 27). ↵

- Teachout and Khan (n 19). ↵